When violence erupts in a healthcare facility, the consequences are many and unpredictable, potentially including injury or death of building occupants; property damage; lawsuits; and diminished patient, staff, and community trust. The risk of workplace violence looms in healthcare facilities—where a stressful work environment can quickly become volatile, visitors may be highly emotional, and drugs or expensive equipment may become targets of robbery. In addition, home care employees may walk alone into homes where patients or their family members keep weapons or drugs or may visit homes in areas with high crime rates, increasing the risk of encountering violence while on the job.

Many violent events in healthcare, particularly assaults on staff members, are caused by patients; however, this guidance article focuses on violence committed by visitors, employees, and trespassers (e.g., robbery, stalking of a patient or employee, intimate partner violence). For more information on violence caused by patients, see

Patient Violence.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health defines workplace violence as "violent acts, including physical assaults and threats of assault, directed toward personnel at work or on duty." Many other sources include verbal aggression (e.g., threats, verbal abuse, hostility, harassment) in the definition of workplace violence. Not only can verbal aggression cause significant psychological trauma and stress, it can also escalate to physical violence. (OSHA "Caring")

Incidence

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) reports that in each year from 2011 to 2013, U.S. healthcare workers suffered 15,000 to 20,000 serious workplace-violence-related injuries; serious injuries are those that require time away from work for treatment and recovery (OSHA "Caring").

Violence is significantly more common in healthcare than in other industries, such that violence-related injuries to healthcare workers account for almost as many similar injuries sustained by workers in all other industries combined. In 2013, healthcare and social assistance workers experienced 7.8 cases of serious workplace violence injuries per 10,000 full-time equivalents (FTEs), while other larges sectors such as construction, manufacturing, and retail all had fewer than two cases per 10,000 FTEs. (OSHA "Caring")

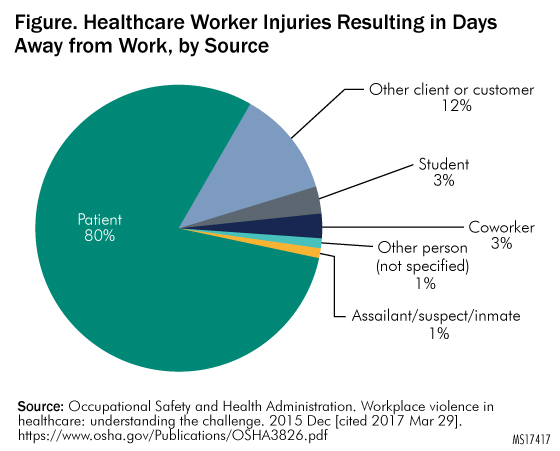

Additionally, in 2016, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) published an analysis of three federal datasets revealing that in 2013 healthcare workers at inpatient facilities such as hospitals experienced injuries from workplace violence that required time off at a rate that was five times that of overall private-sector workers. According to OSHA, individuals other than patients, including visitors and coworkers, cause 20% of violent incidents in healthcare. See

Figure. Healthcare Worker Injuries Resulting in Days Away from Work, by Source for an illustration.

|

Organizational Perspective

In a violence reduction project conducted at a large American hospital that examined employee event reports involving workplace violence, an overall rate of 3.03 incidents per 100 FTEs per year was identified (Arnetz et al. "Application").

Risk Factors

Healthcare workers face serious risks. As Kevin Tuohey, president-elect of the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety, stated in a 2017 publication, "While hospitals have always been looked at as places of refuge, as places that were really safe, I think in the last 10 years that's changed, and I think that they are no longer exempt." (HCPro)

The following risk factors for violence are inherent to the provision of healthcare (Joint Commission "OSHA"; Papa and Venella):

- Setting-specific vulnerabilities of acute care hospitals, emergency departments (EDs), community health clinics, drug treatment clinics, long-term care facilities, and private homes

- Isolated work—conducted alone or in small groups, in remote areas, or in areas with high crime rates

- Late night or early morning work hours

- The "economic realities of healthcare," such as reduction in staff, increased productivity pressure, patients and visitors who are experiencing difficult personal or financial circumstances

- Exchange of money with the public

- Transport and delivery of passengers, goods, or services

High-Risk Areas

Certain clinical areas are particularly vulnerable to violence perpetrated by a family member or visitor.

Emergency department. Several factors predispose the ED to violence. As the main route of public access into the facility, EDs are often understaffed and overcrowded. The American College of Emergency Physicians posits that an overall increase in violence throughout society has, in turn, increased violence in hospitals and EDs. The organization cites the following factors that increase the risk of violence in EDs (ACEP "Emergency"):

- Presence of gangs

- Long wait times for care, sometimes in undesirable environments

- Influence of drugs and alcohol

- Private citizens arming themselves

- Presence of individuals requiring "medical clearance" after an arrest by law enforcement

- Presence of individuals requiring psychiatric support in absence of sufficient dedicated mental health facilities

In one survey, more than 75% of emergency physicians reported experiencing at least one incident of workplace violence per year; nearly as many emergency nurses reported verbal or physical assault by patients or visitors. (ACEP "Emergency")

In a study of ED resident physicians published in 2016, in addition to reporting varying levels of violence perpetrated by patients, subjects reported experiencing the following types and rates of violence perpetrated by visitors (Schnapp et al.):

- Verbal harassment: 86.6%

- Sexual harassment: 21.8%

- Physical violence: 11.8%

Perhaps not surprisingly, nearly a quarter of the residents surveyed reported feeling safe at work "occasionally," "seldom," or "never." (Schnapp et al.)

Women's healthcare. Women's healthcare—including labor and delivery and the maternal-child health unit—is a high-risk environment owing to the emotionally charged issues surrounding pregnancy and childbirth. (Papa and Venella)

Intensive care unit (ICU). Because the ICU cares for the most seriously ill patients, visitors to this area may be extremely distraught, stressed, and demanding of staff attention, which may—or may appear to be—in short supply. This combination can lead to verbal aggression toward staff and can escalate into physical assault, especially if staff are not properly trained in responding to distraught visitors.

Neonatal or pediatric ICU. Concerned parents may become violent while waiting to talk to a physician, while waiting for test results, or after finding out that their child has an serious disease. Divorced or estranged parents may come into conflict over their child's care in nurseries or on pediatric floors; custody disputes may spill over into the hospital.

Policies on how to deal with estranged parents should be in place, as well as procedures for proving that abuse-protection and custody orders are valid. For more information on security measures used to prevent babies from being improperly removed from the hospital, see

Preventing Infant Abductions.

Parking lots and other exterior areas. Several factors can contribute to a parking area becoming the scene of violence. Parking areas may be dark, may offer many hiding places, and may be deserted at certain hours.

Home care. Home care workers, who often must enter patients' homes alone, are particularly vulnerable to violence. Home care workers may be exposed to unsafe conditions and have reported feeling threatened when they know that loaded weapons are present in a patient's home, or that drive-by shootings or gang violence have occurred in the neighborhood. Rats, other vermin, or hostile animals may be present, or housing may be in a deteriorated condition, or other situations may exist that suggest the potential for physical violence, verbal abuse, or sexual harassment by patients, family members, or visitors (Gershon et al.). For more information on risks and strategies for home care workers, see the guidance articles

Home Care: An Overview and

Home Care: Staff-Related Risks, and the self-assessment questionnaires

Home Care: Management and Operations and

Home Care: Staff-Related Risks.

Types of Workplace Violence

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) classifies workplace violence according to perpetrators, as follows (FBI "Violence"):

- Type 1: Violence perpetrated by criminals who have no connection with the workplace (e.g., thieves)

- Type 2: Violence perpetrated by those whom an organization serves (e.g., patients, families, visitors)

- Type 3: Violence perpetrated against coworkers, supervisors, or managers by a present or former employee

- Type 4: Violence perpetrated by someone who has a personal relationship with an employee (e.g., an abusive spouse)

Type 1 violence accounts for only a small number of healthcare workplace violence incidents. Type 2 violence is the most common cause of physical violence in the healthcare setting, and type 3 violence is the most prevalent type of healthcare workplace violence. (Wax et al.)

A violence reduction project conducted at a large American hospital found that 64% of incidents against healthcare workers were perpetrated by patients or their visitors (type 2), while 35% were perpetrated by coworkers (type 3). Additionally, researchers identified surgery as the sole clinical area in which incidents perpetrated by coworkers (type 3) outnumbered incidents perpetrated by patients (type 2) (Arnetz et al. "Application").

Although the prevalence of type 4 workplace violence specific to healthcare is unknown, such incidents do occur. Moreover, the frequency of domestic violence perpetrated against women, in combination with the typically large proportion of female workers in healthcare organizations, creates the "potential for serious events." (Sawyer)

Incident Types

Healthcare workers may experience a range of violent acts. To understand the experiences of hospital nurses who responded to a validated electronic survey regarding violence perpetrated by visitors, see

Table 1. Type of Violence Perpetrated by Visitors.

|

Type of Violence Perpetrated by Visitors |

Percentage of Nurses Experienced |

| Verbal abuse | 32.9% |

| Shouting or yelling | 35.8% |

| Swearing or cursing | 24.9% |

| Physical abuse | 3.5% |

| Grabbing | 1.1% |

| Scratching or kicking | 0.8% |

Worker Safety

The potential impact of workplace violence on healthcare workers—both victims and witnesses—is significant in both the short and long term. In addition to the most immediate consequences of psychological trauma, physical injury, or even death, affected healthcare workers report feelings of anger, shock, hurt, frustration, embarrassment, humiliation, and depression. (Wax et al.) A literature review on workplace violence in healthcare identified the following responses, likely to impact quality of care, for affected workers (Phillips):

- Increase in missed workdays

- Burnout

- Job dissatisfaction

- Decreased productivity

- Decreased sense of safety

- Increased self-protection with personal weapons (e.g., knives, firearms)

Patient Safety

Violence in the healthcare workplace, by its very nature, can put both patients and healthcare workers at risk. This may happen overtly, such as when a patient and a nurse's aide "were shot and killed for no apparent reason" by an armed man at a Florida hospital in 2016 (HCPro).

Impact on patients can also be more subtle; violence in healthcare settings has many potential downstream effects. For example, a negative relationship has been reported between violence experienced by healthcare workers and patient-perceived quality of care (Arnetz and Arnetz). Additionally, worker-to-worker incivility in the operating department has been linked to a poorer safety climate and decreased compliance with recommended practices in the surgical environment (Hamblin et al. "Catalysts").

Danger in the Absence of Physical Aggression

Regardless of whether physical aggression is involved, verbal threats are associated with independent risk for workplace violence. Verbal assault is a risk factor for battery and future serious incidents of violence (Phillips; Schnapp et al.). Research also shows a "significant relationship between hospital workers who were subject to verbal assault by a colleague and the risk of work-related injuries" (Hamblin et al. "Catalysts").

Costs

Loss of life, injury, and suffering by patients and healthcare workers alike are obvious costs of violence in healthcare—and the financial implications are significant. OSHA reports that just one serious injury can result in workers' compensation losses of thousands of dollars, in addition to thousands more for overtime, temporary staffing, or recruiting and training a replacement. (OSHA "Prevention") The overall cost associated with workplace violence to all American businesses—not exclusively healthcare—is an estimated $120 billion a year (Papa and Venella).

Potential hidden costs that organizations may incur include those for counseling affected individuals, the time required for managers and administrators to handle the issue and participate in the investigation, and increased medical claims for stress-related conditions. The publicity that follows a violent act in a healthcare setting can also do long-term damage to an organization's reputation. (Papa and Venella) Other hidden costs include increased worker turnover and decreased productivity and morale (OSHA "Prevention").

Workers' Compensation

In a retrospective database review of violence perpetrated against nurses by patients or visitors in a U.S. urban and community hospital system, annual costs for the 2.1% of nurses reporting workplace violence injuries were $94,156, including $78,924 for treatment and $15,232 for indemnity (Speroni et al.).

Lawsuits

Litigation that follows acts of workplace violence is a "major direct cost." The average jury award in workplace violence cases in which an employer failed to take proactive, preventive measures has been reported as $3.1 million per person per incident. (Papa and Venella)

Three police officers employed by a Michigan hospital sued the owner of the parent medical system for $1 million each in 2016, alleging that they faced retaliation in response to filing complaints about crime and violence on the hospital campus. One of the officers reportedly questioned, "Hospitals are supposed to be safe havens. If we, as the first line of defense, aren't safe, how are we going to keep patients and their visitors safe?" (Kurth)

Federal Law

The general-duty clause of the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSH Act) broadly addresses a multitude of workplace safety issues by requiring employers to furnish employees with employment and with a place of employment free from recognized hazards that cause or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm (29 USC § 654[a][1-2]).

Courts have interpreted the general-duty clause to mean that an employer has a legal obligation to provide a workplace free of conditions or activities—for example, workplace violence—that either the employer or industry recognizes as hazardous and that cause, or are likely to cause, death or serious physical harm to employees when there is a feasible method to abate the hazard. OSHA can cite and fine employers who fail to take reasonable steps to prevent or abate a recognized violence hazard in the workplace. (OSHA "Fact Sheet")

OSHA Guidance

In 2016, OSHA released updated

guidance on preventing violence in healthcare and social service settings. The guidance is advisory in nature; it is not a standard or regulation, and it does not create new legal obligations or alter existing obligations created by OSHA standards or the OSH Act. (OSHA "Guidelines") However, it does provide a wealth of practical strategies for violence prevention.

There have been signals that OSHA's protection of the healthcare workforce may become increasingly robust. For example, in a 2016 report, GAO recommended that OSHA increase its education and enforcement efforts; OSHA agreed and stated that it would take action to address the following steps (GAO):

- Provision of additional information for inspectors on developing citations

- Follow-up on hazard alert letters

- Assessment of efforts to address workplace violence in healthcare settings to determine whether additional action is needed

Furthermore, OSHA is also considering the need for a specific standard to protect healthcare workers from workplace violence. In 2016, the agency published a request for information in the

Federal Register, seeking public comments on the extent and nature of workplace violence in the healthcare industry as well as the nature and effectiveness of interventions and controls for violence prevention. (OSHA "Prevention") The American Hospital Association has argued against the need for such a standard (American Hospital Association).

OSHA Reporting and Record-Keeping

Violent events that result in worker or staff injuries requiring treatment beyond first aid or requiring days away from work must be reported to OSHA, per agency standard (29 CFR § 1904). Employers must record these injuries in the OSHA Form 300 Log of Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses. Employers must report all work-related fatalities within 8 hours of learning of them, and must report the following occurrences within 24 hours of learning of them (OSHA "Updates"):

- All work-related inpatient hospitalizations of one or more employees

- All work-related amputations

- All work-related losses of an eye

For more information on OSHA's record-keeping standard and injury reporting forms, see

OSHA Illness and Injury Record-Keeping Standard.

OSHA Inspections

OSHA may conduct an inspection in response to complaints or reports of workplace violence. According to Joint Commission, the agency typically evaluates the need for an inspection according to the following factors (Joint Commission "OSHA"):

- Involvement of a known risk factor

- Evidence—or lack thereof—that the organization recognizes the potential for workplace violence

- Potential methods to address the hazards that lead to violence

For example, OSHA is more likely to inspect following a violent incident involving a known risk factor if previous incidents have occurred and potential methods existed to alleviate the risk factors (e.g., an attack on a nurse by a patient's family member who has a history of violence toward staff), as opposed to following a random act of violence. (Joint Commission "OSHA")

Federal Fines

Healthcare organizations that fail to properly protect employees from the dangers of workplace violence face the threat of being fined by OSHA. For example, a Pennsylvania home care provider in 2016 was fined nearly $100,000 after a home care worker was sexually assaulted. The agency found that the organization failed to provide an effective workplace violence prevention program even in the face of numerous reports of verbal, physical, and sexual assaults on employees. (OSHA "Federal Inspectors")

In 2014, OSHA fined a New York hospital $70,000 for willful failure to protect employees from assaults by patients and visitors, substantiated by 40 incidents of violence by patients and visitors in a three-month period. Given that many employees were unaware of its existence or purpose, OSHA found the organization's workplace violence prevention program ineffective. (OSHA "Brookdale")

State Law

State law may provide additional protection for healthcare workers. Some states— including Maine, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Illinois, Washington, Oregon, and California—have enacted laws that require employers to establish comprehensive workplace violence prevention programs for healthcare employees. Others have increased penalties for those convicted of assaulting a nurse or, in some cases, other healthcare workers. The laws vary in scope and groups of individuals protected. (OSHA "Workplace Violence Prevention")

Such laws have proven effective in lowering injury rates and workers' compensation costs. For example, in Washington State, a 28% decrease in the rate of workers' compensation claims in the healthcare and social assistance industry occurred after a state rule took effect requiring hazard assessments, training, and incident tracking for workplace violence. (OSHA "Workplace Violence Prevention")

State Fines

State regulators may levy fines for failure to protect employees from workplace violence. For example, in 2016, investigators identified 116 injuries related to patient and visitor violence at a Detroit hospital between 2012 and 2015 (Kurth). The Michigan Occupational Safety and Health Administration imposed a $5,000 fine and required implementation of a plan to address routine exposure of healthcare and security employees to violent behavior by patients and visitors (Rege).

Joint Commission

The following Joint Commission standards address workplace violence in accredited healthcare settings (Joint Commission "Comprehensive"):

- Standard LD.03.01.01 requires leaders to create and maintain a culture of safety and quality throughout the organization, which impacts both patient and worker safety

- Standard LD.04.04.05 requires an organization-wide safety program, and requires systems for blame-free incident reporting

- Standard EC.02.01.01 requires organizations to manage safety and security risks

- Standard EM.02.02.05 requires organizations to maintain emergency operations plans describing how the facility will coordinate security activities with community security agencies

Additionally, Joint Commission considers the "rape, assault (leading to death or permanent loss of function), or homicide of a staff member, licensed independent practitioner, visitor, or vendor while on site at the health care organization" to be a sentinel event (Joint Commission "Sentinel").

DNV

Det Norske Veritas Germanischer Lloyd (DNV-GL) quality management standards require accredited hospitals to "maintain safe and secure facilities that are designed and maintained in accordance with national and local laws, hospital policy, regulations and guidelines." Standards further specify that "the Security Management System shall address issues related to abduction, elopement, visitors, workplace violence, and investigation of property losses and [shall] be proportional to the risk." (DNV-GL, PE 4, SR 3)

Professional Associations

Professional associations including the American College of Emergency Physicians, the American Nurses Association, and the Emergency Nurses Association have issued policies, position statements, and resources regarding workplace violence. See

Resource List for more information.

Establish

Policies and Procedures

Action Recommendation: Develop and enforce comprehensive policies and procedures against workplace violence.

Organizations should develop and enforce comprehensive policies and procedures, such as the following, against violence perpetrated by visitors, staff, patients, or other individuals. All policies concerning violent events should be applied consistently to all individuals.

Zero tolerance. A zero-tolerance policy, which states that any form of violence is not acceptable, applies to all employees, patients, and visitors (ACEP "Protection"). Although zero tolerance does not mean that violence will not happen, it sets the expectation that violence will not be tolerated and will be dealt with according to policy. Such a policy should explicitly acknowledge verbal assault as a form of violence, because tolerance of verbal abuse and low-level battery invites more serious forms of violence (Phillips). The policy should also specify actions that are grounds for termination or discipline (e.g., committing an act of violence, failing to report an act of violence) (Hamer).

Mandatory reporting. A mandatory reporting policy requires all staff to report any actual or threatened physical or verbal assault without delay (ACEP "Protection").

Nonretaliation. A nonretaliation policy should explicitly forbid any adverse employment action (e.g., actual or threatened termination, demotion, suspension, discrimination) against an employee for good-faith reporting of actual or threatened violence (ACEP "Protection").

Response to violence. Procedures for responding to incidents of workplace violence should clearly address designated employee roles and responsibilities for notifying managers and security, activating emergency response codes, and incident reporting. All employees should receive instruction on these procedures.

Assess Data

Action Recommendation: Evaluate objective measures of violence to identify risks and risk levels.

The ECRI Institute PSO event database contains reports of violent incidents in healthcare such as the following: - The father of a patient physically assaulting his child’s physician

- A patient’s family member assaulting a nurse before being arrested by the police

- Multiple reports of visitors assaulting other visitors—charging, punching, kicking, and grabbing

- A visitor making abusive and racially charged comments to a nurse’s aide

- A physician threatening to “punch (a piece of equipment) through the wall”

|

To determine a healthcare facility's risk of violence and develop prevention strategies, risk managers should partner with the security department to conduct a review of facility and community records and statistical crime rates. An internal or external event reporting system can be instrumental in this assessment. By looking for patterns and determining root causes, risk managers can glean insights into vulnerabilities. See

Violent Events Reported for a sampling of violent events reported to the ECRI Institute Patient Safety Organization (PSO).

Risk managers should not only review documentation of previous violent acts within the facility but also collect statistics on violent gang activity, drug abuse, and other such issues in the community. Records for review include existing documentation, such as the OSHA log, union information, incident reports, workers' compensation or other insurance reports, minutes from safety and risk management meetings, security reports, and suggestions from employees. (OSHA "Caring") Risk managers can ask the local police department and emergency management services to provide a community crime profile, which should include the number and types of criminal offenses committed in the vicinity of the facility and the times of day when incidence of violent crime is the highest. (Wax et al.) Risk managers can also consult local businesses and other area healthcare facilities about the amount of violence in and around their establishments, read national news for trends in violent crime, or research U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data to identify trends in comparable locations with similar populations.

To get a more complete list of possible risks, risk managers may conduct a survey asking workers, volunteers, and contractors to identify specific violence risks or concerns. For example, while there may be no history of assaults in the parking lots, employees may be afraid to walk there after dark. Once analyzed, data should be used to inform an appropriate action plan and communicated accordingly. For example, it would be helpful for staff to know whether threats have been made against physicians or that the organization serves a high number of patients from correctional institutions. (HCPro) However, such information would likely be alarming in the absence of an appropriate organizational response. Risk managers can also use the self-assessment questionnaire

Violence Prevention to identify strengths and weaknesses and improve the organization's violence prevention program.

Promote Recognition of Potentially Violent Individuals

Action Recommendation: Train staff to recognize the warning signs of violent behavior and respond proactively.

Distraught Family Members and Friends

Uncertainty, grief, and frustration experienced by patients' family members and friends can translate to physical or verbal aggression toward staff members, patients, or others. For example, in Alabama in 2012, a 38-year-old man who was reportedly unhappy with the care that his wife—a cardiac patient—was receiving arrived at a hospital at 4 a.m. with a gun. The man opened fire, shooting a police officer and two hospital employees. Police returned fire and the man was killed. (PRI)

An ECRI member asked us for information regarding procedures for searching hospital visitors.

See our response. |

Violence may also be committed by distraught family members of patients who have died or who have been discharged from the hospital. In a widely publicized 2015 incident, the son of a former patient shot and killed his deceased mother's cardiologist in an exam room at a Boston hospital. According to published reports, the man arrived at the cardiologist's office without an appointment, demanding to meet with the physician. The cardiologist agreed, and for more than half an hour he answered the man's questions about a drug that had been prescribed to his mother before her death. After 15 minutes, the cardiologist dismissed his physician's assistant, requesting that she check on other patients. Twenty minutes later, shots were heard from behind the door of the exam room. The cardiologist emerged injured and collapsed. The patient's son killed himself. After eight hours of emergency surgery, the physician died. (Sweeney)

Although cases of family violence may be difficult to prevent, healthcare staff can look for warning signs that may indicate an increased risk of family violence and take steps to de-escalate a family member's behavior. For example, family members who are excessively stressed may exhibit early warning signs such as rapid pacing, excessive fidgeting, shouting, or depression (Barthel; Barboza and Zarembo).

In some cases, taking family members to a safe, quiet area to help calm their emotions or arranging a meeting with a supervisor to help answer the family members' clinical questions can help defuse emotions (Barthel). In addition, a family member who spends most of his or her time at the facility, who visits the facility at odd hours, or who attempts to access restricted areas of the facility may be more prone to violence (Barboza and Zarembo; Kaldy). For more information on recognizing potentially violent behavior, and use of de-escalation techniques, see

Patient Violence.

Individuals Affected by Intimate Partner Violence

Patients who present to the hospital ED may be there because they have been injured by their spouse or partner, who may follow the patient to the healthcare facility and cause a violent episode. Identifying a victim of intimate partner violence can be challenging because clinical presentation varies widely. However, providers can include screening questions for domestic abuse in the intake process during discussion of the patient's medical history, social history, or history of present illness, whichever seems most appropriate and is most comfortable for the provider. See Recognizing and Responding to Intimate Partner Violence for more information. Healthcare workers may themselves be victims of intimate partner violence and could be targeted at work by their abusers (i.e., type 4 violence). Supervisors should be trained to detect warning signs that employees are experiencing domestic violence and to refer employees to the employee assistance program (EAP). Some common signs that should raise a supervisor's suspicion that an employee may be a victim of abuse are as follows ("Protecting Domestic Abuse Victims"):

- High rates of absenteeism and tardiness

- Direct evidence of physical or psychological interference by the employee's partner (e.g., employee makes or receives an excessive number of personal calls, or partner visits unannounced)

- Behavioral changes (e.g., the employee appears nervous, complains of chronic ailments, or has an obvious change in appearance or personality)

- Decreased productivity and difficulty concentrating and performing normal duties

Patients or healthcare workers may also become victims of stalking. Patients are particularly vulnerable while in a hospital bed. Patients should be encouraged to report threats against them during the intake process (e.g., show protection orders). Patients who report being threatened or stalked should be placed in a room that can be easily and constantly monitored. Of course, this type of information must be treated as confidential. Only with assurance of confidentiality will patients or healthcare workers come forward with this information.

The following actions have been recommended if an employee is being threatened or stalked (Kelley; Kinney):

- Relocate his or her workstation

- If the threat is acute, give the employee time off

- Provide photographs of stalkers to receptionists and security officers

- Encourage law enforcement to enforce restraining orders

- Place silent alarms at the employee's workstation

- Deploy security cameras near entrances to the employee's workstation

- Provide protective services

Workers Who Victimize Coworkers

Worker-to-worker violence includes physical assault, verbal aggression, harassment, intimidation, threats, and bullying. It may be perpetrated by senior staff towards junior staff, or between employees of the same professional rank (e.g., "horizontal" or "lateral" violence). (Hamblin et al. "Catalysts")

A qualitative content analysis of employee incident reports of worker-to-worker violence and incivility documented in a large metropolitan hospital system in 2011 revealed that over 50% of incidents involved nurses. The majority of incidents did not involve physical violence; however, some did, such as the following situations (Hamblin et al. "Catalysts"):

- "Pharmacy technician was in the medication room completing 'cart exchange.' During her duties, she was approached by a nurse who grabbed her hands/wrists, stopped her from completing her duties, while she questioned her about her activity. Technician explained her duties and nurse finally let go."

- "Security officer entered the unit and was in the process of restraining a patient when it was noted that he had his weapon still on. When asked to leave the unit, he responded 'It's not loaded'; when asked to leave again he became angry and threw a watch across the nursing desk, pulled off his gloves and threw them, hitting one of our nurses in the head."

A study of violent incident reports from a large hospital system's human resources database revealed perpetrator characteristics of worker-to-worker (i.e., type 3) violence, defined as physical assault, verbal aggression, sexual harassment, intimidation, bullying, and threats. Researchers found that perpetrators of type 3 violence in healthcare were typically female, full-time workers and were more likely to be nurses or patient care associates. The following were identified as the five most common perpetrator-target dyads (Hamblin et al. "Worker"):

- Nurse to nurse

- Patient care associate to nurse

- Allied health professional to nurse

- Medical resident to nurse

- Nurse to patient care associate

Healthcare organizations must take precautions to minimize the risk of violent behavior from staff members. The stressful healthcare environment can increase the chance that individuals who usually do not demonstrate violent tendencies will act violently.

Drug and alcohol abuse (to which many healthcare workers may be vulnerable owing to the stressful nature of their occupation) exacerbates the risk. See

Substance Use Disorders in Nurses and

Substance Use Disorders in Physicians for more information.

However, employees generally do not just "snap"—red flags usually appear first. Supervisors and employees should be advised of signs that an individual may become violent. See

Table 2. Signs That an Individual May Become Violent for behavioral and physical signs as described by the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety (CCOHS).

| Behavioral signs |

Physical signs |

| Crying, sulking, outbursts | Flushing, pallor, sweating |

| Frequent lateness or absenteeism | Tired appearance |

| Poor work quality; denial of work performance problems | Clenched muscles (e.g., fists) |

| Belief that he or she is always correct | Making violent gestures |

| Poor handling of criticism | Rapid, shallow breathing |

| Blaming others for errors | Scowling, sneering, glaring |

| Testing limits | Avoidance of eye contact |

| Use of curses and other inappropriate communication | Restless or repetitive movements such as pacing |

| Difficulty with concentration and recall | Shaking, trembling |

| Social isolation | Vocal changes |

| Complaints of unfair treatment | Chanting or speaking loudly |

| Hyperfocus on problems, without resolving them | Invading the personal space of others |

See Resource List for information on other warning signs of a potentially violent person provided by CCOHS.

Staff should be educated about warning signs of potential violence and instructed to inform their supervisor if an employee exhibits any of these indicators of potentially violent tendencies. The supervisor should maintain confidentiality by first talking to human resources staff or a representative from the EAP about the staff concerns and behaviors that have been reported. However, if the healthcare worker is creating a hostile work environment—or if the reported behavior poses an immediate threat to patient or staff safety—the behavior must be addressed immediately.

Supervisors should refer employees who exhibit warning signs of potential violence to the facility's EAP for assistance when appropriate. As discussed above, healthcare workers and staff members not normally prone to violence may unpredictably lash out due to workplace or personal stressors. EAPs can contribute to minimizing the risk of this type of violence and may offer individual counseling or family counseling.

Disciplined or Fired Employees

A healthcare worker who is fired or disciplined could potentially perpetrate retaliatory violence, especially if he or she exhibits indicators of violence before the firing or disciplinary action. Risk managers should ensure that supervisors give all employees notice of organizational policies and procedures and the corresponding disciplinary actions for violation. This forewarning can prevent employees from feeling singled out if disciplined. If an incident that may require discipline or termination occurs, supervisors should investigate the situation to get the employee's side of the story, and ensure consistency in the treatment of all employees. Supervisors should be trained in how to discipline and fire employees without triggering a violent outburst and should partner with human resources staff. (Proskauer Rose)

Healthcare organizations may consider providing job counseling through the EAP for terminated or laid-off workers. This shows that the organization cares, and it may reduce hostility levels. When potentially violent or highly disgruntled employees must be terminated, staff may prevent a violent response by making eye contact, by allowing the employee to communicate his or her feelings, by listening attentively and paraphrasing what is being said, by empathizing but not apologizing, and by always asking if the employee has further questions before closing the meeting (Johnson et al.). After the employee's termination, a security officer or member of management should be available to escort the employee back to his or her desk and then to the door of the building. Identification cards and badges should be returned, computer identification passwords should be deleted from the system, and methods for access to the building or campus should be changed as necessary. The facility may also wish to organize a meeting with staff members to inform them of the termination (without providing confidential or unnecessary information) and remind them of which procedures to take if they notice a terminated employee near the facility or campus.

Employees Who Harm Patients

Purposeful patient harm is a rarer, more sinister manifestation of violence by healthcare workers. Most healthcare workers are dedicated, caring individuals; however, no organization is immune to an exception. For example, according to published reports, in 2013 an Oregon jury awarded $2.4 million to three women who alleged that they had been the victims of inappropriate sexual contact by an anesthesiologist while incapacitated by sedatives or anesthetics. The plaintiffs, who sued the hospital where their procedures took place as well as the hospital's chief executive officer and vice president/risk manager, alleged that the hospital had sufficient information to act against the anesthesiologist years before his eventual arrest. In total, 19 women, including patients and hospital staff, alleged abuse by the physician. ("Claims Against Hospital")

The plaintiffs received $700,000, $800,000, and $900,000 respectively; two other women reached confidential settlements with the hospital; and other cases were pending at the time of the report. The physician pled guilty to 11 counts of sexual abuse and one count of rape; he was sentenced to 23 years in prison. ("Claims Against Hospital")

Enforcing stringent background check procedures is key to preventing patient harm. One of the most accurate predictors of harmful or violent behavior is a history of violence or implication in a suspicious patient injury or death. If an event involving employee violence does occur, it is important, from a liability standpoint, for the healthcare facility to be able to show that it did everything in its power to screen out employees with a violent past. For a more detailed discussion on conducting background checks, refer to

Criminal Background Checks. Healthcare employers whose workforce includes healthcare providers and practitioners obtained through temporary staffing agencies may have a duty to ensure that the temporary employment agencies they use have obtained criminal background records. For more on this topic, refer to

Employing Temporary and Agency Staff. However, background checks are not foolproof safeguards against hiring employees who may become violent. Risk managers must work with supervisors to ensure they treat employee reports of suspicious behavior seriously, investigate reports thoroughly, and never react negatively toward the reporting employee. In alarming cases, workers continued to maliciously harm patients because warning signs went unnoticed or were ignored by other employees, supervisors, and healthcare facility administration.

Establish a Violence Prevention Program

Action Recommendation: Establish a comprehensive workplace violence prevention program.

Despite the prevalence of violence in healthcare, research on prevention has not yielded universally applicable strategies for risk reduction (Phillips). However, OSHA has identified the following five core elements of a comprehensive workplace violence prevention program that can form the basis for organization-specific prevention strategies (OSHA "Caring"):

- Management commitment and employee participation

- Worksite analysis and hazard identification

- Hazard prevention and control

- Safety and health training

- Record keeping and program evaluation

Management Commitment and Employee Participation

Leaders, supervisors, and staff each play critical roles in the development and execution of a robust workplace violence prevention program.

Leaders. According to OSHA, leaders should begin the development of a workplace violence prevention program by convening a planning group or task force to collect baseline data, plan, implement strategies, and monitor the program. Whoever leads the group should have the appropriate knowledge base and the appropriate authority to effect the necessary changes. (OSHA "Caring")

Leaders should also build a multidisciplinary threat assessment team, which often includes representatives from the behavioral sciences, security or law enforcement, labor union(s), high-risk areas, staff education, patient advocates, and legal counsel. Typically, an organization's chief medical officer leads such a team with support from senior clinicians (e.g., behavioral science professionals) who are trained in threat assessment. (Wyatt et al.)

In addition to establishing a violence prevention program and a threat assessment team, leaders can demonstrate commitment through the following actions (Wyatt et al.):

- Encouraging the reporting of violence and safety events

- Providing reassurance that appropriate action will be taken

- Engaging all stakeholders in safety plans

- Assessing performance of violence prevention programs

Supervisors and staff. OSHA also cites the importance of a "participatory approach [in which] employees and management work together on worksite assessment and solution implementation." Suggested areas for representation on workplace violence prevention committees include direct care staff; human resources, safety, security, and legal departments; unions; and local law enforcement. (OSHA "Caring") As the individuals on the front lines of care and interaction with visitors, family members, and coworkers, direct care workers have valuable input on the problem of workplace violence.

When supervisors engage staff to review incidents of violence, they should discuss how situations fall outside of established norms and strategize to prevent future incidents. The benefit of this collaboration is twofold: First, supervisors will promote a culture of civility and empowerment in the workplace; in so doing, supervisors will also help to prevent future harassment or violence. (Hamblin et al. "Worker;" Phillips)

Worksite Analysis and Hazard Identification

A team including clinical and nonclinical employees, security staff, supervisors, and senior management should assess risks for workplace violence through a workplace security analysis, record review, employee surveys, and job analysis. Such an analysis may yield information on risk factors including the following (OSHA "Caring"):

- Environmental hazards (e.g., poor lighting, poor environmental design, working in areas with high crime rates)

- Interpersonal hazards (e.g., working with distressed individuals, working with individuals who have a history of substance abuse or violence)

- Organizational hazards (e.g., understaffing, long wait times, emphasis on customer satisfaction over staff safety)

A workplace security analysis, or "walk-through," should cover all internal and external areas, with a special focus on areas identified as high risk. The assessment team should include frontline healthcare workers with nurse representatives from each unit and safety and security professionals. Any deficiencies documented during the walk-through should be addressed immediately to avoid liability in the event of violence. During the walk-through, employees may be questioned about relevant details. The team should try to assess issues such as prevailing style of management, areas of excess stress, and ways in which individuals organize their duties. Attention should be given to questions such as the following:

- Are windows and doors secure?

- Are security guards or other individuals trained to respond to an emergency violence code?

- Is training provided in de-escalation and nonviolent crisis intervention?

- Are patients' valuables stored in a secure place?

- Are staffing levels adequate, especially during meal times or visiting hours?

- Is access to floors being monitored?

- Is equipment secure (e.g., sharps are properly stored)?

- Are rooms laid out to prevent entrapment (e.g., examination room exits are unobstructed)?

- Are bulletproof vests available or necessary?

- Are mechanisms in place to relieve overcrowding of high-traffic areas?

- Is lighting adequate?

- Are staff lounges locked?

- Are private areas available for distraught family members?

- Are panic buttons located at nursing stations and registration desks?

- Are in-house emergency call numbers posted for all staff to summon help?

- Are all access areas monitored and controlled?

- Is appropriate signage in place and legible?

- Are monitoring devices in place and operable?

During the walk-through, employees should be asked the following questions:

- Are you ever totally alone on the unit?

- Are you ever out of hearing or sight of other workers?

- Is there anything about your physical work environment that could contribute to an assault?

- Do you know the emergency codes and how to respond to violence?

- Have you had any violence-related training?

Staff should be surveyed during all shifts and situations (e.g., holidays, emergencies). On holidays and third shifts, staff shortages may make organizations more vulnerable to violence. During emergencies, people are usually so involved with response efforts that they may forget procedures that protect against violence. The self-assessment questionnaire

Violence Prevention and sample policy Workplace Violence Prevention Plan can be used to further identify and document the strengths and weaknesses of the facility's violence prevention program. Additionally, OSHA's "Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence for Healthcare and Social Service Workers" contains program assessment checklists; see Resource List for details.

Workplace Violence Prevention Plan can be used to further identify and document the strengths and weaknesses of the facility's violence prevention program. Additionally, OSHA's "Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence for Healthcare and Social Service Workers" contains program assessment checklists; see Resource List for details.

Hazard Prevention and Control

Once hazards are identified, OSHA recommends addressing them with a combination of engineering controls and administrative and work practice controls. Brief examples of engineering controls—physical changes to the workplace—include the following (OSHA "Caring"):

- Installing mirrors and security technologies

- Controlling access to high-risk areas

- Protecting nurses' stations with enclosures or deep counters

- Improving lighting

- Modifying floor plans for better lines of sight and access to exits

Examples of administrative and work practice controls—changes to the way staff perform their jobs—include the following (OSHA "Caring"):

- Conducting threat assessments—and periodic reassessments—to evaluate the potential for violence

- Ensuring adequate staffing at all times

- Conducting training in de-escalation techniques and related skills

- Enforcing policies and procedures that are designed to minimize stress for patients and visitors

See

Hospital Security for a detailed discussion on hazard prevention and control in the healthcare workplace.

Safety and Health Training

Training is an essential component of any comprehensive workplace violence prevention program, so that staff are competent to recognize warning signs, know how to respond, and are confident in doing so. OSHA states that many training programs, policies, and procedures focus only on violence committed by patients, and in so doing fail to address violence by employees, random criminals, and perpetrators of intimate partner violence. Therefore, risk managers should ensure that training covers all types of workplace violence as opposed to only violence perpetrated by patients against employees. (OSHA "Caring")

Although the importance of training the workforce in policies and prevention strategies may seem obvious, these steps cannot be taken for granted. For example, in one survey of ED resident physicians, only 16% of subjects reported prior training in violence prevention or de-escalation techniques. Researchers found this result to be in concurrence with other reports on training of ED physicians (Schnapp et al.)

Similarly, in a study of workplace violence prevention programs at California home care and hospice agencies, only 77.5% of the organizations reported having policies in place to protect workers from violent or aggressive patients. Additionally, just 35% reported training employees in factors predicting violence and aggression; fewer trained workers on de-escalation or self-defense, and only 15% provided training for all employees participating in patient care. (Gross et al.)

Although all staff, affiliated physicians, and contract workers should be trained in prevention and response to workplace violence, training should also be tailored according to duties and work locations. OSHA recommends customizing training to the particular needs of nurses and other direct caregivers, ED staff, support staff, security personnel, and supervisors and managers. (OSHA "Caring")

For example, supervisors and managers, who have higher levels of responsibility as agents of the employer, should be trained separately from staff; they should be informed that all reports of suspicious behavior or threats must be treated seriously and thoroughly investigated. Areas for emphasis include the following (Hamer):

- Recognizing potential violence in the early stages

- Enforcing policy adequately

- Fostering a culture in which reporting is encouraged and retaliation is unacceptable

Security personnel are critical responders in violent or potentially violent situations. They should receive specialized training to address "the psychological components of handling aggressive and abusive clients" and instruction in techniques for managing aggressive individuals and defusing hostile situations. (OSHA "Guidelines")

Some training topics suggested by OSHA for all staff, affiliated physicians, and contract workers include the following (OSHA "Caring"):

- Information regarding safety devices such as alarm systems

- Warning signs of situations that may lead to assaults (e.g., escalating behavior)

- Use of de-escalation techniques, self-defense strategies, and other approaches to address volatile situations or aggressive behavior (for more information on de-escalation techniques, see

Patient Violence)

- Approaches for responding to aggressive behavior in individuals other than patients

- The importance of seeking assistance promptly

- Strategies for self-protection, including working in teams and accessing areas that can provide shelter from violence

- An action plan for responding to violent incidents

- Policies and procedures for reporting, record keeping, and seeking support (e.g., medical care, counseling, workers' compensation, legal assistance) after a violent event

The most successful training programs for workplace violence prevention utilize a variety of formats including classroom training, hands-on instruction, real-time (i.e., "just-in-time") coaching, and periodic refresher training. Although OSHA acknowledges several advantages of web-based training, the agency recommends blending any remote training format with live instruction and practice opportunities—essential elements for skill building. (OSHA "Caring") Such in-person training provides critical opportunities for employees to practice individual roles and responsibilities as delineated by organizational policy for violence prevention and response. Because violence management training is learned, not innate, practice and refresher training are critical to maintain learned skills.

Record Keeping and Program Evaluation

Employee reporting of incidents and near-misses is a critical first step for accurate record keeping and program evaluation. Yet, underreporting is a challenge. Leaders and supervisors should stress the vital importance of record keeping as a foundation for program evaluation, to assess program efficacy, identify overlooked hazards, establish training needs, and pinpoint additional preventive measures (OSHA "Caring").

See

Encourage Reporting for more information. Violent events that result in worker or staff injuries requiring treatment beyond first aid or requiring days away from work must be reported to OSHA, per the agency's standard for reporting and recording work-related illness and injury (29 CFR § 1904). See

OSHA Illness and Injury Record-Keeping Standard for more information.

Encourage Reporting

Action Recommendation: Encourage all employees and other staff to report incidents of violence or any perceived threats of violence.

Reporting, which is critical to the success of a workplace violence prevention program, depends on efficient and effective event reporting systems from which leaders can glean insights for intervention and prevention (Wyatt et al.). However, underreporting of workplace violence by healthcare workers is a major issue. Employees may fear supervisors will blame them or minimize the seriousness of an incident; they may also be reluctant to cause tension, or they may blame themselves. See

"UNDERREPORTING" Violence in the Healthcare Workplace for nurses' reasons for not reporting workplace violence. The organization's policy against retaliation should address these concerns.

The reporting of workplace violence in a seven-hospital system with approximately 15,000 employees was studied using a subset of data from the organization's electronic incident reporting system, which included only workplace violence events. Frequency of reporting (or lack thereof) was determined by comparing employee self-reports in a study questionnaire against documented incidents in the electronic reporting system. Despite organizational policy mandating the reporting of violence, researchers identified an 88% rate of underreporting. Interestingly, although this translates to a reporting rate of 12%, 23% of respondents who self-reported experiencing workplace violence indicated that they had reported via the electronic system. (Arnetz et al. "Underreporting")

At a large academic level I trauma center in the Midwest, a quality improvement project identified the organization's "cumbersome online reporting process," which takes 15 to 20 minutes to complete, as a barrier to reporting workplace violence. The project team created an "informal reporting tool" that takes 1 to 2 minutes to complete, and provided a comprehensive educational program addressing workplace violence and how to report it. Reporting increased from zero reported workplace violence events in 2012 to more than 50 reports filed the following year. Furthermore, and considered the project's "greatest success" by the project team, the percentage of staff who considered workplace violence to be part of the job decreased from nearly 56% to just over 24%. (Stene et al.)

Employees should be educated on the organization's definition of violence and encouraged to report to their supervisor or other designated individual anything they perceive as a warning sign of violence. A hotline can also be used for this purpose. The system should protect the confidentiality of employees who make written or verbal reports. All reports should be documented and should result in immediate action, to ensure safety and facilitate continued reporting. Increasing the frequency of violence reporting will better equip the healthcare facility to implement effective measures for reducing the risk of violence. Reporting will be maximized when reporting systems are simple, trusted, and secure; when they allow for anonymity; when they are fully supported by leadership, management, and labor unions; and when they result in transparent outcomes (Wyatt et al.). See

Event Reporting for more information.

Respond Appropriately

Action Recommendation: Ensure appropriate follow-up to violent events, including communication, postincident support, and investigation.

Despite a healthcare organization's best efforts, violent events are bound to occur. Appropriate postincident support for employees who are victims of violence includes first aid, prompt medical treatment, debriefing, counseling, and employee assistance (ACEP "Protection"). Most importantly, organizations need to be cognizant of the impact of workplace violence on the individual healthcare worker, and provide appropriate support and ongoing resources (Papa and Venella).

First aid and medical care. First, victims must be attended as required by their physical condition, whether with first aid or more comprehensive medical evaluation and treatment. The area should then be cleaned (e.g., blood, broken glass, and sharp objects removed).

Communication. Next, information should be disseminated to appropriate individuals regarding what happened, what actions will be taken against perpetrators, and what steps the facility will take to prevent a recurrence. Periodic progress updates may be indicated.

Procedures should be in place to guide the release of information to media representatives. The more violent the event, the more the media will be attracted. See

Media Relations for more information on this topic.

Employee support. Counseling or critical-incident stress debriefing should be available to employees who are victims of, involved in, or witnesses to violent events. Certified employee assistance professionals, psychologists, psychiatrists, clinical nurse specialists, or social workers should provide this counseling.

The facility may also refer employees to outside specialists for this need. Some employees may prefer peer counseling or employee support groups. Employees may fear returning to work or even suffer posttraumatic stress disorder; it may be beneficial to allow victims to transfer to a different work area if desired. It is imperative that employees involved in violent events, whether as victims or tangentially, feel supported and never feel that they are being blamed. Victims of violence should be encouraged to use the EAP even if they are not certain that it is necessary. (OSHA "Guidelines")

Investigation. Once the safety of all involved has been ensured, an investigation should be conducted. Important steps include notifying appropriate individuals within and outside the organization, involving workers from the affected area, identifying root causes, reviewing related records (e.g., prior incident reports), and investigating near misses. (OSHA "Guidelines") See

Getting the Most out of Root-Cause Analyses for more information.

Thorough documentation and investigation of the violent episode can provide a silver lining to an otherwise negative situation. By identifying contributing factors—inadequate security, failure to investigate complaints of suspicious behavior, physical features of the facility—the organization can develop controls to prevent a recurrence.

Acknowledge Threat of Shooting Incidents

Action Recommendation: Ensure that the violence prevention program addresses the possibility of gun violence, including active shooters.

An ECRI member asked us for information regarding safety concerns with use of tasers on patients.

See our response. |

Hospital-based shootings are relatively rare in comparison with other violent events in healthcare settings, yet they have obvious potential for grave consequences. In a study conducted to identify U.S. acute care hospital shooting events between 2000 and 2011, researchers identified 154 incidents. Approximately 60% of shootings occurred within the hospital; the remainder took place on hospital grounds. The most common sites were the ED (29%), the parking lot (23%), and patient rooms (19%). Researchers found that the majority of events involved a "determined shooter with a strong motive," such as a grudge (27%), suicide (21%), mercy killing (14%), and prisoner escape (11%). (Kelen et al.) Not all of the shootings in this study fit within federal law enforcement's definition of "active shooter" incidents.

Some hospital-based shootings qualify as "active shooter" incidents. An active shooter is "an individual actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people in a confined and populated area." In comparison to a murder or mass killing, the word "active" indicates that law enforcement personnel and private citizens have the potential, based on their responses, to affect the outcome of the event—possibly saving lives. (Blair and Schweit)

FBI has created a repository of active shooter incidents in the United States occurring between 2001 and 2016; six of these incidents occurred in healthcare settings. Although none occurred before 2009, since then an active shooter incident has occurred in a healthcare setting almost every year. See Table 3. Active Shooter Incidents in Healthcare Facilities for more information.

|

Year |

Location |

Incident Details |

2009 | Carthage, NC | A man armed with a handgun, a shotgun, and a rifle arrived at a skilled nursing facility looking for his estranged wife, who was an employee there. He did not find her, but he killed eight people. Three others were wounded, including one police officer. The shooter was apprehended after being wounded during an exchange of gunfire with police. |

| 2010 | Knoxville, TN | A former patient who was unhappy with the outcome of a recent surgery arrived at a hospital looking for his doctor. When unsuccessful, he proceeded to the emergency department and opened fire. He killed one person and wounded two others. He committed suicide before police arrived. |

| 2012 | Birmingham, AL | A man who was unhappy with the care provided to his wife arrived at the hospital armed with a handgun and began shooting. Three individuals were wounded, including one police officer. The shooter was killed by police. |

| 2013 | Reno, NV | A former patient who was reportedly unhappy with results of a surgery three years prior entered a hospital armed with a shotgun and two handguns. He killed one person and wounded two others before committing suicide. |

| 2014 | Darby, PA | A patient armed with a handgun entered his psychiatrist’s office and began shooting. He killed his caseworker and injured the doctor. The psychiatrist—who was licensed to carry a firearm—returned fire, wounding the shooter. |

| 2015 | Colorado Springs, CO | A man armed with a rifle allegedly killed three people, including a law enforcement officer, at a women’s health clinic. Nine others were wounded, including five law enforcement officers. The shooter eventually surrendered to law enforcement. |

Additionally, in 2016, a patient and a nurse's aide "were shot and killed for no apparent reason by an armed man" who entered a Florida hospital. According to published reports, the hospital's active shooter plan, which had been in place for eight years, was instrumental in avoiding further loss of life. Furthermore, the hospital has reportedly taken additional security measures since the shooting, including the following (HCPro):

- Maintaining law enforcement presence with enhanced security at public entrances

- Requiring identification before granting access at the main entrance and ED

- Conducting random checks of bags

- Arming security officers with additional protective equipment and gear

- Providing security officers with additional training

In 2014, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in collaboration with several other federal agencies, released a guide on how to incorporate planning for an active shooter incident into healthcare facility emergency-operations plans. Although such an event is "still an anomaly in the healthcare setting," this training is an important part of a comprehensive workplace violence prevention program (Hartley). See

Resource List for additional information.

For more information on planning for active shooter incidents, see

Preparing for an Active Shooter Incident and

Hospital Relations with Police.

Organizations should evaluate a range of environmental and administrative controls (e.g., panic alarm systems, protective barriers, increased security presence) to decrease the risk of gun violence, as part of the comprehensive violence prevention program. Considering metal detectors may be part of this planning process, with individual, location-specific factors taken into account. However, metal detectors can be expensive to maintain and can raise liability issues. Unless all entrants are scanned, the facility could be liable for discriminatory scanning or for failing to detect a weapon later used in a violent event. Personnel are required to monitor machines, and entrances without machines would need to be closed. Given the relative rarity of this type of violence, and citing a lack of concrete evidence to support the expectation that metal detectors decrease violence in healthcare settings, researchers have acknowledged that "metal detectors may not be the best use of safety resources" (Phillips). For more information on physical security solutions, see

Hospital Security.