Burnout: A Primer

A "complex syndrome of emotional distress" due to occupational factors, burnout is characterized by feelings of fatigue, cynicism, and decreased self-efficacy. Burnout disproportionately affects individuals who work in healthcare and is associated with low job satisfaction, increased medical errors, alcohol and substance abuse, and impaired interpersonal relationships. (Elmore et al.)

Burnout results from a mismatch between an individual's values and one or more of the following aspects of his or her employment experience: workload, perceived control over work experiences, rewards for work, sense of community, perceived fairness in the workplace, and personal ethics and values (Maslach et al.).

Healthcare workers who experience burnout typically exhibit the following (Drill-Mellum and Kinneer):

- High levels of depersonalization—for example, seeing patients as diagnoses, rather than individuals

- High levels of emotional exhaustion resulting from physical and emotional overload

- Low levels of personal accomplishment, causing individuals to question their judgment and decisions

Burnout among physicians is not only alarmingly prevalent, it is on the rise: 54.4% of surveyed physicians reported at least one symptom of burnout in 2014, an increase from 45.5% in 2011 (Shanafelt et al. "Changes"). Certain subsets of physicians experience even higher rates of burnout. For example, in a national survey, 69% of 655 general surgery residents in the United States met criteria for burnout on at least one subscale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (Elmore et al.). The Maslach Burnout Inventory, the most widely used research measure of burnout, utilizes three subscales: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment. See

Figure 1. Burnout at a Glance for more Information.

Not Just Physicians

Figure 1. Burnout at a Glance

Click for complete image. |

Although much research on burnout in healthcare workers has focused on physicians, concern is growing about burnout in other healthcare workers as well. For example, in a recent ECRI Institute survey on the topic, almost as many respondents were concerned about burnout in nonphysician providers (29%) and support staff (27%) as in physicians (33%).

Experts agree. Sue Boisvert, BSN, MHSA, CPHRM, FASHRM, senior risk specialist at Coverys, reports that, in the course of her professional duties, she works with a lot of highly functioning organizations that "do a great job from start to finish." But some of her own experiences advocating for a family member in need of care have given her a different perspective on the topic of burnout.

Historically, Boisvert observed burnout as a problem in physicians. However, although she "cannot be sure of a relationship," she has noted both increased burnout in nurses specifically and "increased inclusion of nurses in litigation—which used to be rare."

In a 2014 analysis of registered nurses and respiratory therapists working in the intensive care unit (ICU), 54% scored "moderate" to "high" for emotional exhaustion on the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Forty percent scored "moderate" to "high" on depersonalization, and 40.6% scored "low" on the personal accomplishment scale. Nurses' overall level of burnout and depersonalization was higher than that of respiratory therapists. (Guntupalli et al.)

Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah has recently undertaken research to evaluate staff burnout and "compassion fatigue," discipline by discipline. The project has yielded "interesting data," reports Lawrence Marsco, MSN, OCN, RN, nurse manager of the intensive care unit at Huntsman. For example, preliminary findings at the facility suggest that "pharmacists are at risk of burnout as well," Marsco states. In addition to the often emotionally challenging clinical work with patients, Marsco notes, pharmacists working in oncology "sometimes also have to address financial issues—the astronomical costs of cancer medication—with patients and families. It's an added stressor."

Not Just Clinicians

Boisvert questions whether risk managers themselves are burned out. "If you put a group of risk managers in a room, more than 50% will [report] examples of poor care experienced personally or by a family member: the humanity is gone from healthcare," she says, though she is quick to reiterate that she sees wonderful staff in high-performing organizations. "Not entirely, but a noticeable amount of the humanity is gone."

An

HRC member who did not wish to be identified concurs: "Risk managers and patient relations staff have a steady diet of negative work."

"Burnout doesn't affect a specific 'type' of worker," notes Laurie Drill-Mellum, MD, MPH, chief medical officer and vice president of patient safety at Constellation/MMIC/UMIA. Rather, all healthcare workers are at risk, including nonclinicians.

"Housekeepers," for example, "are just as vulnerable as the rest of the staff," says Marsco. "They're in the room with patients and families for 15 to 20 minutes every day," he shares. They develop close relationships and experience deep loss when patients pass away. Some have needed to rotate out of the ICU, Marsco reports.

"Unit secretaries get to know the families really well and that's just as hard," Marsco adds. They're often there when family members need to step out of their loved one's room for a bit of respite, he explains, and they may become a sounding board or offer a chance to "vent." In Marsco's view, potential for burnout "includes anyone who might interact with patients or families." Boisvert agrees that burnout is also a problem for support staff, citing nursing assistants and medical assistants as examples. Frequent interaction with unhappy patients, families, and staff can also take a toll on receptionists, who are often the proverbial first line of defense.

Causes and Symptoms

Historically, healthcare workers have been at risk of burnout owing to characteristics of the healthcare environment such as role conflict, poor relationships between groups and with leadership, and the emotional intensity of clinical work (Lyndon). For example, occurrences such as a patient's death, participating in a discussion about end-of-life care, performance of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and adverse events can all be extremely stressful for the clinician(s) involved. Cumulatively, events such as these can lead to burnout.

At present, though, burnout is also an unintended consequence of healthcare transformation. System-generated stressors, including cost cutting, ever-increasing regulation, and the evolution of the electronic health record (EHR), have resulted in "an erosion of control" and an abundance of new tasks for providers—without any more time to accomplish their work. (Dunn et al.; Sinsky et al.) Constant change, which has become "the new normal," can be taxing for even the most dedicated healthcare workers.

Anne Shirah, RNC, MSN, CPHQ, director of quality services and risk manager at Monroe County Hospital in Alabama, believes that patient acuity, especially given the current regulatory environment, is the driving factor behind burnout in nurses: "The main thing is that the acuity of patients is so high. They're so sick and have to meet so many government criteria to actually be admitted. An assignment now is nothing like it was even ten years ago."

Boisvert agrees. "Complexity is a big part of the problem," she states.

Shirah, who practiced bedside nursing for nearly 30 years before transitioning to quality and risk management, reports that nurses continue to work in long-standing nurse-to-patient ratios. Yet, she cautions, "now the patients are so much sicker and nurses have less support," such as from aides.

Source: ECRI Institute HRC member survey, October 2016.

Source: ECRI Institute HRC member survey, October 2016. |

Clinicians spend a significant portion of their workdays entering information into the EHR. Correlations have been established between burnout and increased task burden for EHR documentation. In at least some cases, "EHR time" far exceeds direct time with patients. For example, a quantitative direct observational time-and-motion study of ambulatory care physicians revealed that they spend 49.2% of their time on EHR and desk work, and 27% of their office day on direct clinical face time with patients. A smaller sample of physicians who completed after-hours diaries reported that they faced an additional one to two hours of computer and clerical work each night. (Sinsky et al.)

Clinicians are also significantly impacted by "work compression," the imperative to do the same work in less time (Shin et al.). A host of quality initiatives and regulatory requirements create more and more work to be accomplished, while the EHR already consumes a large portion of working hours. At the same time, cost-cutting measures often preclude the hiring of additional help. "Government regulations are a huge problem," states Shirah.

An

HRC member concurs, stating, "Our physician hotline receives calls from [our organization's] physicians and their office managers, exasperated by all of the changes and government regulations. Prior to EHRs, physicians would not be required to spend evenings and weekends scribing . . . They could spend more time with patients and do wellness activity in their spare time. [Now] we hear from physicians that they have no wellness time."

Shirah sees many healthcare professionals overloaded with a multitude of roles and duties: clinicians who are tired, under pressure, attempting to keep up with the rapid pace of change, and afraid of making a mistake. Workers are, as one physician says, "moving so fast we can barely breathe" (Wallach). Or, as Shirah reports, "too exhausted to stop and talk." In some cases, she sees these factors manifest in an inability to focus; in other cases, they lead to complacency. See

Fatigue in Healthcare Workers for more information.

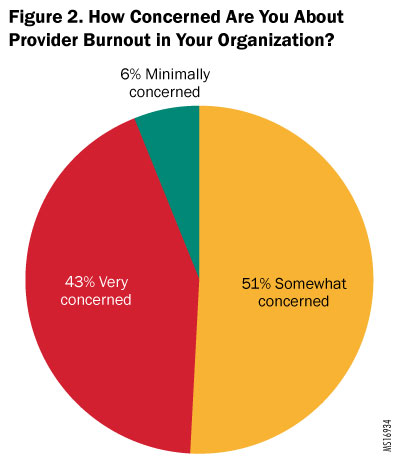

Consensus is growing both in the literature and among

HRC members that the "burnout epidemic" is a significant problem in the healthcare industry. See Figure 2. How Concerned Are You About Provider Burnout? for more information. However, many in the industry continue to attribute the problem to individual clinicians' inability to adapt to changing priorities. This is troubling because it not only downplays the genuine stress that healthcare workers experience, it also questions and reprimands struggling individuals. (Shin et al.)

Risk Management Implications

The medicolegal and financial implications of provider burnout are important for providers and organizations because they "extend to patients in measureable ways" (Shin et al.). These implications have been demonstrated in various studies, including the following:

- Physicians who experience burnout are more likely to be disengaged from patients and colleagues and to make diagnostic and safety errors (Shin et al.)

- One-point changes in burnout scores have been associated with "meaningful differences" in self-perceived major medical errors, suicidal ideation, and reduced work hours (West et al. "Interventions to Prevent")

- Nurse dissatisfaction and burnout have been linked to suboptimal care and low patient satisfaction (Cimiotti et al.; McHugh et al.)

- Nurse burnout is significantly associated with hospital-acquired infections (i.e., urinary tract infection and surgical site infection) (Cimiotti et al.)

Shirah sees a connection between burnout—and factors leading to it—and patient safety. For example, most of the medication errors that she reviews result from nurses "not paying close enough attention." She attributes this to nurses having too much to do, and being exhausted from their workloads. See

Burnout-Related Events Reported to ECRI Institute PSO for a description of patient safety concerns related to burnout.

Burnout is also associated with reduced empathy for patients, reduced patient satisfaction, decreased patient adherence to treatment recommendations, and increased physician intent to leave the practice, which can be staggeringly expensive for organizations. For example, the cost of replacing a single physician frequently exceeds $500,000. (Linzer et al. "Preventing;" Smith)

Correspondingly, the potential exists to positively impact clinical and financial outcomes by managing burnout: one study of the relationship between hospital-acquired infections and burnout in nurses found that a theoretical 30% reduction in nurse burnout—and corresponding reduction in infections—would result in an annual total cost savings of up to $68 million among the 161 Pennsylvania acute care hospitals in the study sample (Cimiotti et al.).

A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout, published in September 2016, found that both individual and organizational strategies can yield "clinically meaningful reductions in burnout among physicians." No specific interventions were more effective than others; however, the researchers felt that both types of strategies—individually focused and organizational—were likely necessary. The authors called for further research to determine efficacy in specific populations and combinations of strategies. (West et al. "Interventions to Prevent")

Imperative for Organizational Change

A query of ECRI Institute PSO's database of more than 1.2 million patient safety events using the terms "burnout" and "overwork" identified multiple concerns, including the following:

- A strong theme of nurses reporting that both professional and support staff are chronically and significantly understaffed, resulting in caregiver burnout and turnover as well as harm to patients

- An allegation that a physician being overworked and rushed was a factor in an adverse surgical event

- A respiratory therapist telling a nurse—in front of a patient and his family—that she was "already overworked" and would not be able to fulfill a prescribed increase in nebulizer treatment frequency

- A chaplain who refused a family's request that he visit their loved one, stating that he was burned out and had already visited the patient once

|

It is clear that healthcare workers need help. However, it needs to be the right kind of help. Attempting to bolster individual resiliency—without addressing the stressors that lead to burnout—sends a questionable message about the causes of burnout as well as the role of the individual in addressing it. Transferring this "responsibility onto the most powerless in the system" could actually be counterproductive. (Wallach)

Therefore, to facilitate meaningful improvement, it is critical to understand that the factors leading to burnout "are rooted in the environment and care delivery system rather than [in] the personal characteristics of a few susceptible individuals." (Shanafelt et al. "Burnout") Although individually focused interventions can be valuable for managing the symptoms of burnout, organizational change—along with individual education—is the only way to truly prevent burnout (Maslach et al.).

A strategy that merely engages frontline workers—"the very people suffering from burnout"—is not likely to be successful in isolation (Shin et al.) For example, offering employees instruction in meditation, in and of itself, is highly unlikely to decrease burnout. Rather, to continue the example, staff would need to be encouraged to attend the class—and allocated time to do so.

Even then, leaders would need to address the systems causes leading to burnout in the first place. Accordingly, many strategies to combat burnout in healthcare workers recommended by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health revolve around organizational change. It really takes leaders—such as medical directors and administrators—to make a difference. (Lindell) Experts acknowledge that given the broad and multifactorial nature of burnout, this amounts to calling for "significant systemic and structural changes to the current health care delivery system." (Shin et al.)

Boisvert echoes the need for systems-level change: "Individual strategies only help one provider, and one provider only impacts a certain number of patients." She compares addressing burnout to other patient safety initiatives, underscoring the need for wide dissemination and acceptance. She states, "You can't count on the few individuals—the self-selected crowd—who already understand the problem and accept the intervention with minimal effort."

Complementing this view, Sinsky (cited in Caplan et al.) theorizes that approximately 80% of the factors leading to burnout are organizationally driven, while approximately 20% can be attributed to individual factors. Therefore, the strategies that I suggest here are weighted heavily in favor of systems-level changes, with a lesser proportion of individually focused interventions.

Organizations can effect much change on burnout, not only by cultivating a "just culture" that is supportive of workers—the necessary foundation for all patient safety and quality initiatives—but also by taking specific, observable actions when setting organizational priorities and objectives. This may include initiatives to address contributing factors (e.g., productivity mandates) as well as those that specifically address burnout. For example, as an

HRC member stated, "Productivity is valued by many, but I don't know if the bedside physician, midlevel practitioner, or nurse ever [has] input into productivity calculations, some of which are unrealistic."

To that point, organizations should consider involving frontline clinicians in the planning stage of system changes, to ensure "that such changes always foster, rather than impede, the delivery of compassionate care that is both physician- and patient-centered" (Shin et al.).

By involving staff in organizational changes from the beginning, listening to staff concerns, and giving staff "the opportunity to have a voice in decisions and actions that directly affect their jobs," leaders can mitigate downstream effects of change (Lindell). Staff who have had the opportunity to provide input are also more likely to accept—and even embrace—a change. Truly understanding the role of frontline staff and involving them in organizational change is a "priceless" part of her organization's "constant efforts toward a just culture," Shirah states. Prioritizing initiatives may also be helpful, giving staff the chance to incorporate meaningful change on one initiative before beginning the next.

Many organizational strategies address burnout specifically. Linzer and colleagues have suggested "metrics for institutional success that include physician satisfaction and well-being;" this concept can certainly be expanded to include all employees (Linzer et al. "10 Bold Steps"). For example, Marsco reports that the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah has set an organizational goal to be a "compassionate workplace."

Making social workers and chaplains available to staff for their own needs at any time is another "key" organizational commitment Huntsman has undertaken to support staff through the emotional challenges associated with oncology care, Marsco reports.

Drill-Mellum recommends addressing staff well-being in organizational mission statements. She suggests that organizations maintain a policy of providing access to supportive interventions (e.g., debriefing, employee assistance programs [EAPs]) to all staff and physicians—whether employees or independent contractors. See

The Leading Edge: University of Utah Health Sciences for details on an institution-wide initiative focused on building resilience and maintaining the integrity and value of faculty and staff throughout an entire health system.

Lead by Example

Whether positively or negatively, leaders shape organizational culture. Self-care and requesting help do not come naturally to many healthcare workers, who are trained to think of others first (Wallach). A top-down example with a visible commitment to attacking the underlying causes of burnout can be "instrumental in creating a culture that sustains resilience and supports employee well-being." (Shin et al.)

Experts sound their agreement, sharing a variety of practical strategies for harnessing the power of leadership at various levels. Marsco reports that people frequently ask him "why [he's] so happy." "It makes a huge difference to lead by example," he says. "The mood of the leader will make or break the mood of the unit." He also publishes a weekly blog, a main purpose of which is staff recognition.

Shirah and other leaders at Monroe County Hospital—including those in the C-suite—make a point of recognizing staff for a job well done, and showing appreciation accordingly. For example, Shirah takes time to share with clinicians how well the hospital scores on quality measures. She is certain that "making staff feel valued eases some of the factors that can lead to burnout."

Boisvert notes, "Leadership is obviously important: having visionary physicians in important positions raises the bar for all physicians in an organization." She thinks that people can get burned out if they don't feel valued or listened to. "Having peers in leadership roles who can listen and make a difference is really important," she adds.

Offering the EHR as an example, Boisvert finds that when physicians are actively involved with—and, especially, responsible for—implementation, acceptance is greater and more innovative use results, along with fewer challenges. Accordingly, she advocates the use of "physician champions" for staff well-being. Such an individual—whether physician or other professional—can promote use of wellness resources and model positive behaviors (e.g., leaving work on time). (Linzer et al. "Preventing")

Drill-Mellum encourages leaders to express concern for workers as situations warrant, stating that "negative behaviors multiply in the face of leadership silence." Other leadership strategies for mitigating burnout advocated by Drill-Mellum include the following:

- Approaching situations with fairness

- Role modeling

- Empowering staff

- Defining job roles and clarifying expectations so that staff know where their responsibilities end

- Fostering a positive environment

- Spending time in clinical areas

- Encouraging peer support

Interestingly, although HRC members and interview subjects agreed about the potential for leaders to mitigate burnout, they also expressed recurring concerns on behalf of those very individuals. Boisvert questions the turnover rate of hospital chief executive officers (CEOs): "Are they burned out?" Indeed, an

HRC member reported working for an organization that is in the process of onboarding its fourth CEO—in three years.

Maximize Efficient and Appropriate Use of Resources

Given that time compression, regulatory compliance, and EHR usability are major contributors to burnout, efforts to maximize efficient and appropriate use of staff time and talent can be instrumental. Promoting top-of-license practice—eliminating the need for clinicians to spend significant time on tasks that someone else can do—is a leading strategy. Ensuring appropriate staffing and optimizing workflows are also paramount.

According to Dale Lucht, Lean director for Lehigh Valley Health Network, eight types of waste are common in healthcare, beginning with unused human potential. Organizations can detect this problem, he suggests, by asking, "Are all clinicians working to the top of their license?" For example, are nurses transporting patients instead of performing nursing duties? Are physicians entering data into an EHR that a nurse or medical assistant could enter? Rather than pushing staff to work faster or harder, he states, organizations can eliminate waste by "attacking the non-value-add."

Improving workflows has been called "the most powerful antidote to burnout," increasing the odds of reducing burnout six-fold (Linzer et al. "Preventing"). However, ensuring that operational infrastructures allow clinicians to focus on care delivery—so that they do not spend excessive time working at a computer or looking for information, supplies, or staff—requires finding solutions to help all staff perform their jobs as efficiently as possible (Duffy).

Hiring and staffing also have the potential to positively or negatively affect burnout. "Huntsman Cancer Institute's primary intervention for this issue is to ensure that we have enough staff to do the work," Marsco reports. For example, he looks critically at staffing ratios in comparison to the acuity of the patient population.

Marsco is also very mindful of burnout during the recruiting process, and he critically assesses candidates' ability to manage stress in a high-mortality environment. He shares one of his top interview questions: "What do you do to take care of yourself out of the unit?" He also asks candidates for their thoughts on "working with a lot of death and dying."

"Staffing is such a huge challenge for inpatient units," Marsco states. His unit frequently sends out pages that staff might need extra help, and it's a quandary to ensure safe staffing while not burning out staff by constantly asking them to take extra shifts. He monitors overtime and is conscientious about how much people do. "It's a balance," he adds, one that means he and other unit leaders sometimes have to go on the floor "to prevent the need for more overtime than would be safe." See

Understaffing for more information.

A commitment to optimizing staffing includes planning and working around predictable stressors, to avoid the problem described by an

HRC member: "When people are sick or on vacation, there is not enough staff to cover, which leads to many people working longer hours." While sick time usage is not entirely predictable, for example, planning for contingency staffing during flu season should be possible, working from the reasonable expectation that more patients will need more care, while more staff will also need to call out sick.

The literature cites increased use of advanced practice professionals, increased residency slots, and increased medical school enrollments as potential mechanisms to address the physician shortage and, theoretically, to impact burnout. Boisvert has seen hospitals attempt to use these strategies, as well as increased collaboration with medical schools—and she has concerns. She feels that expecting physicians to perform additional supervisory duties, in combination with already heavy workloads and burdensome regulatory requirements, may create "a perfect storm."

Inefficient workflows and redundant processes not only prey upon staff time and energy, they can be a major source of frustration. An organizational commitment to improving cumbersome workflows is another way to mitigate and prevent burnout (Barnet; Duffy).

Improving workflows can also improve patient safety. Shirah notes that staff develop "workarounds" in an attempt to manage or compensate for processes that complicate their workflow. Recognizing this and then working with frontline staff to ensure that processes are both as safe and as straightforward as possible is a key strategy to support clinicians, she says.

Harness the Power of Mentoring

Research indicates—and experts agree—that the way clinicians are trained and the availability of mentors have the potential to positively impact burnout. For example, emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were associated with increased number of work hours per week in general surgery trainees; work hour reform did not appear to have a positive effect on burnout. However, researchers found that a structured mentoring program was associated with a lower proportion of residents meeting the criteria for burnout. (Elmore et al.)

Boisvert agrees and sees the "need to find a different way to deliver care, not just new delivery models." She proposes starting with how providers—especially physicians—are educated. "Reduction in duty hours isn't the answer," she states; residents need more supervision from experienced mentors and "there aren't enough to go around." Comparing this issue to the evolution of hospitalist and laborist roles, Boisvert suggests that physicians who specialize in educating and supervising residents could be helpful.

Shirah concurs that the opportunity to observe and emulate a strong role model helps new physicians develop good habits that are protective against burnout. "You can tell when a physician's attending taught them well—it makes a big difference," she states. Mentoring for nonphysician providers can also be explored.

Promote Engagement through Resiliency Interventions

Engagement is the opposite of burnout, and a variety of interventions to bolster resilience can facilitate engagement in healthcare workers. Interventions known to build job engagement include educational interventions, performance feedback, and social support (Cimiotti et al.). Engaged clinicians are less likely to leave their jobs, or the industry (Smith).

For example, a single-center randomized clinical trial of 74 practicing physicians found that a facilitated small group curriculum for physicians resulted in improved meaning, empowerment, and engagement in work as well as reduced depersonalization. Changes were sustained at 12 months after the conclusion of the study. (West et al. "Intervention to Promote")

Physicians were given "protected time" (one hour of paid time every other week) to participate in a curriculum that included mindfulness, reflection, shared experience, and small group learning. Individuals in the control arm, who were also given protected time to use however they felt it would be most useful—but did not participate in the formal curriculum—did not experience improvement. Researchers found "potential" for "institutional commitments to physician well-being programs to offer at least partial solutions to the current crisis of physician burnout and dissatisfaction." (West et al. "Intervention to Promote")

In the ICU at Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah, "Between the nature of the cancer process and the critical illness that accompanies admission to the unit," states Marsco, "a high mortality rate is the nature of the business." One of the many strategies he uses to help staff cope with this reality is to take time at each quarterly staff meeting to remember and honor the patients they've lost.

On a much lighter note, Marsco also facilitates engagement with a quarterly "fun" outing for his team; recent events include getting together for a meal and going bowling.

One on one, Marsco keeps staff engaged and involved through proactive communication. He has an open-door policy and staff know that they can come in and "cry, scream, and vent" if they need to. "I'm not just the boss," he says, "I'm someone to talk to."

Healthcare organizations should also consider sponsoring, hosting, or otherwise facilitating resiliency interventions in small group formats. Such programs offer benefit not only from structured curriculums, but also from peer support. For example, pediatrics residents at Mattel Children's Hospital UCLA in Los Angeles receive four months of resilience training based on a Department of Defense program for active-duty military personnel and their families. In New York City, residents, fellows, nurses, and social workers from the oncology unit of Mount Sinai West attend hour-long monthly breakfasts that provide the opportunity to process difficult medical events from the preceding weeks. (Lagnado)

Organizations may also wish to consider providing access to stress management services (e.g., debriefing, group sessions, individual counseling) and mental health services; providing stress management and peer support training; implementing a critical-incident stress management program and a program for personnel who are "second victims" of adverse events; and proactively approaching personnel who may be experiencing stress. A sampling of programs includes the following:

- Lumunos is a voluntary program, limited to physicians, with the goal of "help[ing] physicians continue to thrive in what is an imperfect environment." Participants receive a brief weekly email addressing a specific subject related to burnout, and can attend monthly meetings led by a facilitator. A participating physician described it as "a safe place to give honest answers about medicine, patients . . . where everything stays in the room." (Whitman) See "Resource List" for more information.

- "Finding Meaning in Medicine," a program developed by Rachel Naomi Remen, MD, is based on the concept that deep satisfaction in service work (i.e., healthcare) comes from individual discovery of meaning. No-cost monthly meetings—"Finding Meaning" discussion groups—create an opportunity for colleagues to engage in substantive dialogues on chosen topics including grief, courage, and intimacy. Interested clinicians may join an existing support group, or start their own. Although "Finding Meaning" was initially developed for physicians, the program has expanded to include groups for nurses and other healthcare professionals. (Remen Institute) See "Resource List" for more information.

- In Schwartz Rounds, clinicians present a case, which is followed by a facilitated discussion among interdisciplinary providers. Caregiver experiences, attitudes, and feelings receive as much focus as the clinical aspects of the case. (Linzer et al. "Preventing") See

Resource List for more information.

Care for the Caregivers

Physicians, nurses, and other healthcare professionals commonly advise their patients' caregivers to "put the oxygen on yourself first." Ironically, however, healthcare professionals often put their own needs last. Organizations can address and prevent burnout by providing avenues for staff to engage in much-needed self-care, by encouraging staff to avail themselves of these opportunities, and by making it feasible for them to do so.

However, it is critical to remember that individual factors are thought to drive only 20% of the burnout problem. Therefore, individually focused interventions should be the minority of an organization's strategies. Additionally, individual interventions require systems support.

For example, in addition to offering or facilitating individual interventions such as meditation, engaging in regular exercise, and taking brief breaks in a quiet place throughout the day, organizations can prioritize self-care by dedicating protected time and space in which to practice them (Linzer et al. "10 Bold Steps").

As part of its organizational goal to be a compassionate workplace, Marsco reports, the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah Health Sciences has hired a wellness coordinator to oversee upcoming initiatives such as redesign of break rooms to facilitate true relaxation and providing a massage therapist for 10-minute chair massages.

Marsco agrees that individual interventions "must be [supported] top-down." He notes that "it's so important to push staff to take care of themselves," citing as examples his efforts to ensure that his staff always step away, sit down, and eat lunch. On a larger scale, he pushes staff to take their vacation time, and backs his words with action by making sure that their vacations are adequately covered—and, if needed, "putting on [his] scrubs and working with staff to make sure that they can provide safe patient care."

Marsco acknowledges that leaders are at risk for burnout, too; he attributes his own longevity in the field to a mutually supportive relationship with his staff: "They take care of me as much as I take care of them."

The Leading Edge: University of Utah Health Sciences

Robin L. Marcus, PT, PhD, OCS, chief wellness officer for the health sciences at University of Utah Health Sciences, reports that her senior leadership, under the guidance of senior vice president for health sciences Vivian S. Lee, MD, PhD, MBA, is very aware of the national trend—and the patient safety ramifications—of burnout in healthcare workers, and "wants to get ahead of it."

Marcus describes a variety of wellness initiatives at University of Utah Health Sciences in recent years. The health system includes 5 schools and colleges, 4 hospitals, 11 community clinics, a medical group, and a health plan. Individuals served include students, employees, patients, providers, faculty, and staff. A little over a year ago, the organization formed an interdisciplinary committee to address wellness in graduate medical education. This resulted in the hiring of a clinical psychologist—the director of graduate medical education wellness—to develop programming for physical and mental well-being of residents and fellows in collaboration with their program directors.

"This program, along with the need identified by the national data," reports Marcus, "led Dr. Lee to encourage us to begin to assess faculty wellness—and to begin to incorporate wellness as a quality goal for the organization."

Starting with faculty in the School of Medicine, the committee completed burnout assessments, analyzed data, and began to meet with department chairs or their designees to facilitate projects toward the achievement of self-identified goals. The aim, Marcus shares, is to address burnout and the factors associated with it.

Concurrently, complementary initiatives began to flourish within the University of Utah Health Sciences. For example, Carrie Byington, MD, associate vice president for faculty and academic affairs, formed a task force to address faculty resilience. Additionally, the University's Huntsman Cancer Institute adopted an organizational goal to be a compassionate workplace.

These and other initiatives within the University of Utah Health Sciences amounted to "wonderful individual resources" that the university was ready to take to the next level in the form of an "institution-wide initiative." By the very nature of the healthcare industry, Marcus states, the potential will always exist for stressful situations; leadership felt the time had come to "formalize a way of supporting our providers in dealing with them."

Therefore, in late summer 2016, a committee was formed that included the School of Medicine, the Office of Graduate Medical Education, the Office of Wellness and Integrative Health, the Faculty Development Office, and others. That committee, in conjunction with "key players" including but not limited to risk management, human resources, and the EAP, secured approval on a proposal to develop the tentatively named University Health Sciences Resiliency Center. They are "writing job descriptions now," Marcus shares.

According to Marcus, the purpose of the center will be to address resiliency in the entire University of Utah Health Sciences workforce—"not just providers, a comprehensive team approach," she shares. The center will comprise four major programs:

- A "hub" of best practices and innovations for many existing and developing provider and staff wellness initiatives

- A discipline-specific peer counseling program

- A communication skills program

- An on-site EAP on the main campus, in part to address crises but also for preventive services

The center will connect to "typical" wellness interventions on campus, Marcus reports, such as nutrition and exercise initiatives. However, the focus will be on building resilience and maintaining the integrity and value of faculty and staff. The goal is partly accomplished by providing programming for individuals and teams, but addressing "system issues" is also critical. For example, Marcus shares, the center will support other system initiatives such as those addressing EHR optimization so that "physicians can leave work on time and not have to log back on from home."

Back to text