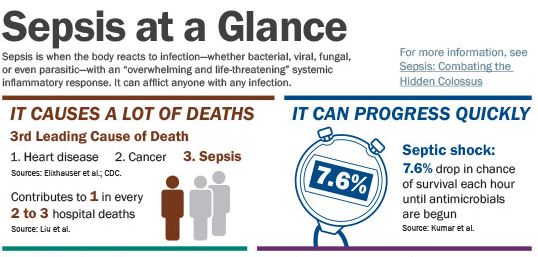

It represents the third leading cause of death (Elixhauser et al.; CDC "Leading Causes"). In-hospital mortality for this condition ranges from 15% to 30% (Gaieski et al.), and it contributes to one of every two to three hospital deaths (Liu et al.). It can strike suddenly and progress quickly; every hour that its severest form goes untreated decreases the chance of surviving by 7.6% (Kumar et al.). It is the most expensive condition treated in U.S. hospitals, accounting for 5.2% of hospital costs nationally, or $20 billion annually (Torio and Andrews).

Ask healthcare professionals or laypeople who hear these statistics to guess which condition they refer to, and "Is it heart disease?" they might guess. "Cancer?" In fact, it is sepsis—a condition that less than half of U.S. adults have heard of (Harris Interactive).

Although very young children, older adults, the immunocompromised, and people with chronic diseases are at greater risk for sepsis, the condition can afflict anyone (CDC "Sepsis Fact Sheet"). See

Sepsis Can Happen to Anyone: The Story of Rory Staunton for an example. Further, says Laura Messineo, RN, MHA, system manager of telehealth operations, Presence Health, it can result from "everyday activities": a cut in the gym, a wound from a house repair, a urinary tract infection. "The more people you connect with, the more you recognize that sepsis can result from any source of infection."

What Is Sepsis?

Sepsis is when the body reacts to infection—whether bacterial, viral, fungal, or even parasitic—with an "overwhelming and life-threatening" systemic inflammatory response (CDC "Sepsis"). It can quickly progress to severe sepsis, which involves organ dysfunction, and then to septic shock, in which low blood pressure does not respond to fluid resuscitation. Death can result. See

Stages and Symptoms of Sepsis for more information.

Stages

and Symptoms of Sepsis |

For sepsis, the treatment may be the same as or similar to the treatment for infection (e.g., antibiotics) but may involve monitoring in the hospital, says Scott D. Weingart, MD, FCCM, chief of emergency critical care at Stony Brook Medical Center and cochair of the STOP (Strengthening Treatment and Outcomes for Patients) Sepsis Collaborative. But with severe sepsis and septic shock, care becomes more aggressive, potentially requiring critical care. Surgery may be needed to address the source of the infection (e.g., an infected appendix).

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign offers two evidence-based bundles (see

Resource List) for addressing severe sepsis and septic shock (Surviving Sepsis Campaign):

- Steps to take within three hours. These include measuring lactate levels, obtaining blood cultures, beginning broad-spectrum antibiotics as an initial therapy, and giving fluids if indicated.

- Steps to take within six hours. These include giving drugs to raise blood pressure if low blood pressure does not respond to fluid resuscitation and reassessing volume and tissue perfusion.

Speedy treatment is vital. Intravenous (IV) antimicrobials are ideally started within an hour of recognition of severe sepsis or septic shock (Dellinger et al.). Starting antimicrobials within the first hour of recognizing septic shock is associated with a 79.9% survival rate. However, survival decreases by 7.6% each hour that antimicrobials are delayed thereafter. (Kumar et al.)

More than 258,000 in-hospital deaths with sepsis listed as a primary or secondary diagnosis occur each year (Elixhauser et al.). If this figure were represented in the list of top causes of death nationally, it would be the third leading cause of death after heart disease and cancer (CDC "Leading Causes").

But even these statistics, as concerning as they are, may underestimate the impact of sepsis. "Sepsis cases are greatly underreported simply because they are classified based on the underlying condition and not sepsis itself," says Pamela L. Popp, MA, JD, DFASHRM, CPHRM, AIM, DSA, executive vice president and chief risk officer, Western Litigation. "Pneumonia? Cause of death is usually sepsis. Postop infection? Cause of death is usually sepsis. Ebola? Cause of death is usually sepsis. And yet most of these are not coded as sepsis, so they aren't in the reported numbers."

Mimi Saffer, vice president of quality improvement and quality measurement, Children's Hospital Association (CHA), agrees. "This whole lack of recognition and lack of response is a counting problem," she says. "It's not coded; it's not on death certificates. It is still not understood to be the scale of problem that it really is."

For survivors, postsepsis syndrome, amputations, and posttraumatic stress disorder are not uncommon. Up to half of sepsis survivors experience postsepsis syndrome, which may include effects such as worsening of cognitive function, hallucinations and panic attacks, severe muscle and joint pain, and fatigue (Sepsis Alliance). Even with insurance coverage, medical bills for treating this costly condition can be ruinous.

Surviving Sepsis: A Risk Manager's Experience describes the lasting repercussions of sepsis for one person with a unique perspective—Popp, a healthcare risk manager.

Click thumbnail for complete image.

|

Why Target Sepsis?

Because of the multifarious risks posed by sepsis, many healthcare organizations and associations have committed to improving its recognition, diagnosis, and treatment.

The high mortality rate is a foremost reason for recent initiatives. "The majority of patient deaths can be traced back to sepsis," says Weingart. "Whether it started that way or ended that way, it's a tremendous source of patient mortality." In fact, he says, "it's the largest source of preventable mortality." Asks Popp: "Where else would we tolerate a mortality rate of 25% or more?"

CHA is motivated to address sepsis because "children's hospitals are at ground zero for the sepsis crisis in children," says Saffer. "Sixty percent of children treated for sepsis are treated in our member hospitals, as many as 25,000 a year. It is the seventh leading cause of death in neonates, and 20% of children admitted to a pediatric intensive care unit for sepsis will die." In addition to being associated with high mortality rates, "half of children are readmitted after surviving an episode of severe sepsis, and 38% experience disability," she adds.

Some also cite the havoc the condition can wreak. "I have personally seen the devastation sepsis brings to patients and families," says Messineo. Popp's employer, Western Litigation, handles claims management as well as risk management, so "I was aware of these cases of patients becoming septic," Popp says. But until she developed it herself, "I had no appreciation for the personal devastation, the financial devastation, or even how often this occurs."

However, sepsis is ripe for intervention because it can be more effectively recognized and treated. "It's the third leading cause of death right now, and it doesn't have to be that way," says Messineo. "With early recognition and prompt treatment, we can improve the outcomes for sepsis patients."

A network of pediatric intensivists that had been working with CHA on reducing central-line infections recommended taking on sepsis using the same improvement science model. "They have been very successful preventing central-line infections, and they believe we can also be effective with sepsis," Saffer explains. "There is also a lot of really good work already happening that we are learning from and integrating into our initiative."

Sepsis presents several challenges to any initiative. "It's hard to find, you have to be fast once you find it, and dealing with it is very complicated," says Saffer. It also requires hospital-wide awareness and a coordinated response. "It involves teamwork across all service lines at the hospital and across all provider specialties," says Popp. "No other condition of this significance requires this type of response—where a missed symptom can cascade the patient into [systemic inflammatory response syndrome] and death in a few short hours."

A Risk Management Perspective

Sepsis poses a spectrum of risks to healthcare organizations. "From a risk management standpoint, it's hard to ignore sepsis," says Popp. Anytime something is associated with high mortality, major liability risks, massive costs for hospitals and patients, or reimbursement challenges, "we should probably take a look at it," she states. Indeed, she says, "sepsis is all of those things."

On the financial side, "every hospital has three buckets of money," says Popp: the operational budget, reimbursement, and the medical malpractice budget. "Sepsis actually covers all three of those buckets."

First, sepsis is "very resource-intensive," sometimes requiring expensive drugs, specialists, and intensive care unit (ICU) care. Second, postoperative sepsis is now a measure included in the hospital-acquired condition payment reduction program. And beginning in fiscal year 2017, adherence to the National Quality Forum's bundle for managing severe sepsis and septic shock (measure number 0500) will be included in the hospital inpatient quality reporting program. (CMS) Third, medical malpractice costs are high. "If you look at verdicts and settlement costs, most are between 1.5 and 20 million dollars," says Popp. "The reason they're so high is that you have a person whose life has been changed, their medical costs are so high, and it's a preventable condition," she states. "There's a tremendous medical malpractice cost to it."

A Need for Speed

With sepsis, prompt recognition, diagnosis, and treatment are crucial. The condition can progress quickly, and "the best interventions are really time-sensitive," Saffer states.

Sepsis needs to be managed like the medical emergency it is. "We have a pretty good community response and facility response when it comes to chest pain," says Popp. Patients are promptly evaluated and, if indicated, given thrombolytic therapy. "We need to have that same kind of approach with sepsis," she says. "There's a window, and there's criteria, and we need to treat you proactively."

Reducing mortality hinges on treating patients sooner. "The most striking result for me was the finding that every hour that care is delayed, mortality goes up 7.6%," says Suchi Saria, PhD, assistant professor of computer science, applied math and statistics, and health policy, Johns Hopkins, a leading expert in machine learning and electronic health record (EHR)–based decision support. "If we could detect these individuals earlier, we could empower clinicians in a new and different way. The opportunity here to improve outcomes is huge." Saria led a team that developed a computer algorithm to pore over a patient's EHR data in real time to assess their risk of developing septic shock. Their computer model identified patients at risk more than a day before septic shock occurred and, in the majority of cases, before they experienced any organ dysfunction. See

The Next Frontier: Using Big Data to Identify Patients at Risk for Septic Shock for more information.

Aside from reducing mortality, speedy treatment reduces the likelihood of progression to septic shock. In addition, much of the neurologic effect seen in postsepsis syndrome comes from the drugs used to treat severe cases, says Popp. These drugs do many of the same things as chemotherapy because they are used to "strip down" and then "reboot" the immune system, she notes. When sepsis is recognized early, "you're treating it with things that are not life-affecting, and you can basically reverse the inflammatory response," she explains.

Messineo similarly likens sepsis to other common medical emergencies. "Just like with stroke or heart attack, the sooner you get in and start getting treatment, the better outcomes you have," she says. "The key is for healthcare clinicians to suspect sepsis in every patient, rapidly screen the patient for sepsis, and implement time-sensitive interventions."

Community Awareness

To optimize the timeliness of treatment, the general public should know the signs and symptoms of sepsis, appreciate the need to seek immediate medical attention, and say to clinicians, "I am concerned about sepsis," as advocated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Sepsis Alliance. However, less than half of U.S. adults have even heard of sepsis (Harris Interactive).

Although many efforts are beginning in hospitals, nonhospital providers, such as primary care practices, specialty physician practices, skilled nursing facilities, home care agencies, and emergency medical services, also play a role. "All of those settings need to be educated on sepsis because it is prevalent in every single one," says Messineo. These settings "could be the first touchpoint within the healthcare system." To give one example, the CHA collaborative will coordinate with emergency medical services and urgent care settings, and future phases will involve prehospital settings (e.g., specialty and primary care clinics) and specialty care hospitals, such as long-term care hospitals.

Healthcare organizations can raise awareness among their patients. Popp advocates putting signs in emergency departments (EDs), other areas of the hospital, urgent care centers, and physician practices, as well as anywhere else healthcare information or education is being shared, listing the signs and symptoms of sepsis and actions to take.

Providers can specifically educate patients who have undergone procedures or are being treated for an infection on the signs and symptoms of sepsis and the need to seek immediate medical attention if they arise. "There is a growing need to proactively educate patients on the early warning signs and distribute awareness materials so they seek medical attention when their condition changes," says Messineo. CDC and Sepsis Alliance offer information and tools for patients and the general public, as well as healthcare providers (see

Resource List). In addition, in the long run, Saria sees a tremendous opportunity for smartphone-based screening tools to raise awareness and aid earlier detection in the community setting.

Organizations can also work to engage the broader community. After five years of educating nurses about sepsis, Messineo says, "I had a point where I felt like I needed to do something more," she says. After attending a Heroes of Sepsis event hosted by Sepsis Alliance, she decided to bring her efforts to the community. "We can make great progress with educating healthcare clinicians, but we also need community awareness of the early warning signs," she notes.

Messineo founded the Illinois Sepsis Challenge, which at the most recent event, in August 2015, included news coverage and a live talkback session. It raised over $38,000 for the Sepsis Alliance, which focuses on increasing awareness of sepsis, especially among the community.

Getting the public to notice signs and symptoms is not the only hurdle. When a child has developed sepsis, for example, "the parents are getting kids to the ED or urgent care because they know something is wrong with their child," Saffer notes. "But they don't know sepsis exists, so they don't know to ask the healthcare providers, 'Look, could this be sepsis?' There are children alive today because their parents asked, 'Have you thought about sepsis?' in the emergency department."

Provider Familiarity

Lack of familiarity with sepsis is not restricted to the community; many healthcare providers are only now gaining a working clinical understanding of the condition and its earlier signs and symptoms. "Up until very recently, treating sepsis was an ED phenomenon and an ICU phenomenon," says Weingart. "On the floors, it was not talked about or really disseminated in educational programs."

One reason is the fact that sepsis screening tools and bundles have been around for only about a decade. Before the availability of screening tools, "maybe we knew the patient was infected, but when they transitioned from routine infection to systemic life-threatening infection was harder to say," says Weingart. It was difficult to tell how seriously ill these patients were until their blood pressure started dropping precipitously and it was obvious something was very wrong.

Even after the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines came out in 2004, says Messineo, "it took some time to educate clinicians." In nursing, "there hasn't been a focus on sepsis education. . . . Some of the first time these nurses are hearing about it is in practice."

But with the availability of evidence-based guidelines and tools, "we're now finding cases earlier and easier, and we can try to treat them before they even get to the point of needing an intensive care unit," says Weingart.

Still, the nature of early signs and symptoms poses hurdles. "One of the biggest challenges is that it's not necessarily easy to diagnose, especially in the early stages, which is when you really want to diagnose it," says Saffer. However, "it's tough to diagnose at that point because it looks like other things." For example, in children. "Fever is one of the hallmarks, but little kids get fever all the time," she notes.

Recognition and Screening

One way to improve recognition of sepsis, especially the early stages, is by improving recognition of the condition and screening for it. "It's important to be screening at every entryway" to the hospital, says Messineo.

Nurses need to know the early warning signs of sepsis, use screening tools as appropriate, and take action if sepsis is suspected. "Nurses are the frontline caregivers, seeing the patient first; we need to empower nurses to suspect sepsis," says Messineo, who educates critical care nurses at Presence Health, which has 11 acute care hospitals in Illinois. "Nurses really have the ability to transform how we deliver care to this patient population." Nurses can also advocate for patients, such as by "saying the word 'sepsis' to other clinicians" when it's suspected. In addition to educating critical care nurses, Messineo has spoken throughout her healthcare system, at other hospitals, and internationally.

Sepsis should be part of periodic training, Messineo suggests. "It needs to be hardwired within the new-hire orientation process," she states. Sepsis can also be included in annual skills days. "It should be a competency for every clinician." Training on a periodic basis also allows incorporation of any changes to evidence-based guidelines to keep everyone up to date.

The CHA collaborative will also focus on "education for all points of the hospital that have to be involved in this," says Saffer. Educational activities and events will be ongoing.

However, "you can't just educate nurses; you have to be able to give them the tools they need so that it becomes part of their daily practice," says Messineo. Prediction tools such as TREWScore, the program that Saria's team developed, can generate a page or an alert in real time as at-risk patients are detected. Other examples include a standardized electronic screening tool or checklist. Presence Health began by screening all patients in the ED and ICU. Later, it implemented the Modified Early Warning Score for medical-surgical patients, which triggers a hard stop for sepsis screening. The system's EDs also have an electronic screening tool embedded in the EHR that triggers a standardized sepsis order set for the physician to consider. The STOP Sepsis Collaborative uses a simple ED nurse triage screening tool; it is available on Weingart's

EMCrit blog (see

Resource List).

Vigilance . . . throughout the Hospital

Another challenge is that "a lot of people with sepsis come through the . . . emergency room, but sepsis also develops on inpatient units," where patients "might not be monitored for escalation into a sepsis state," says Saffer. The signs and symptoms that denote worsening sepsis can be subtle, making it a challenge to spot in the absence of frequent monitoring by knowledgeable providers. A patient with sepsis could be anywhere in-house, so although initial efforts may target specific settings, the ultimate goal should aim for a broader reach.

A corollary, says Popp, is that "no one owns sepsis." Many physicians may feel that sepsis is out of their ken. "There are very few physician specialties that are comfortable dealing with multiorgan failure," says Popp. Yet everyone can diagnose the flu. "Why not get everybody to the same place with sepsis?" and then move them to the right place for treatment, she asks.

Providers are used to ruling out heart attack and stroke. Likewise, "you have to always keep sepsis in mind," Messineo says. "If we cast a wide net, we're going to wind up capturing and treating more of these cases." Popp likewise emphasizes the importance of suspecting sepsis, then ruling it out. Throughout the hospital, this means "everyone watching every patient for early symptoms—without regard to age, gender, or admission diagnosis," she says.

Popp also advocates "respect for the word": if someone says "sepsis," it needs to be considered. "There are some real almost culture pieces that need to change with it," she states. Patients must feel that "it is okay to say to your provider, 'Do you think it's sepsis?'" Popp says, and that "it's not seen as, 'You're overreacting.'"

Beyond "respecting the word," this means taking patients' and family members' concerns seriously. For example, "parents don't know about sepsis by and large, but it's really important to listen to parents saying, 'He's not acting right,'" Saffer notes. "Even though they don't know what sepsis is, they are some of the best people to observe the changes that would happen to a child who is becoming septic."

Once sepsis is recognized and diagnosed, the organization must have physicians who really understand sepsis treatment. "Up until the last couple years, we didn't really have sepsis specialists," says Popp. "We're starting to get them, but a lot of hospitals don't yet have access to them." For children, "having pediatric specialists on the spot who know how to deal with sepsis is so incredibly important," says Saffer. These doctors know which antibiotics to use and at what dosage and how to optimize fluid management.

Evidence-Based Care

A key goal in treating sepsis patients is "making sure the blood circulating through their body is getting enough oxygen perfusion to their tissue," says Weingart. "It's tough convincing people to do it because it's hard."

The healthcare system has effective, efficient responses for treating medical emergencies like heart attack and stroke. But with stroke, for example, "it's an obvious problem and obvious solution," says Weingart. Compared with sepsis, "some of those things are really straightforward," says Saffer. By contrast, "the best interventions for sepsis are fairly complicated." As Weingart says, "You have to work much harder to get [sepsis] patients sound and get everyone educated throughout the hospital."

One strategy may include keeping sepsis protocols as simple as they can be while remaining effective. Participants in the STOP Sepsis Collaborative "kept telling us, 'Make it simpler,'" says Weingart. So, for example, the collaborative eschewed the insertion of central lines for monitoring central venous pressure and oxygen and chose to go with empiric doses of fluids. "We tried to make it really easy." Weingart's

EMCrit blog links to the collaborative's protocols, which are aimed at use in EDs (see

Resource List).

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign, which is an initiative of the Society for Critical Care Medicine, offers guidelines for managing severe sepsis and septic shock. The guidelines are appropriate for use in ICUs, but they can also be used or adapted for other care settings. In fact, the authors note, "the greatest outcome improvement can be made through education and process change for those caring for severe sepsis patients in the non-ICU setting and across the spectrum of acute care" (Dellinger et al.). The campaign's bundles have been updated since publication of the most recent version of the guidelines. See

Resource List for more information.

Interventions can make a difference. For example, a study of 165 sites adopting Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundles—including hospital ICUs, EDs, and wards in the United States, Europe, and South America—found that unadjusted hospital mortality decreased from 37% to 31% over two years. This finding was observed despite only 31% compliance with the resuscitation bundle and 36% compliance with the management bundle at the end of the two-year period. (Levy et al.) In one study of treatment for severe sepsis and septic shock in the ED, patients who received early goal-directed therapy in the ED had an in-hospital mortality rate of 30%, while those who received standard therapy had a mortality rate of 46% (Rivers et al.). And as of June 2013, hospitals in the STOP Sepsis Collaborative had seen a 23% drop in mortality from severe sepsis (McKinney).

Coordination

Protocols for sepsis diagnosis and treatment cannot be implemented in isolation. "You need a very complex process to kick in that's highly coordinated," says Saffer. The STOP Sepsis Collaborative, for example, drew together multiple disciplines, including doctors, nurses, the laboratory, the pharmacy, and risk management. "It was an incredibly iterative process," says Weingart.

The laboratory and pharmacy, in particular, may need to provide test results and drugs much more quickly. For example, because high lactate levels are often a key marker of severe sepsis, one lesson learned from the STOP Sepsis Collaborative is the importance of guaranteeing a 30-minute turnaround for lactate testing or investing in point-of-care lactate testing. "It's totally cost-effective" compared with having sepsis go unrecognized for hours, Weingart says.

Initiatives may also need to address multiple care settings within the hospital. A team of more than 60 sepsis experts from about 40 hospitals are working on the design of CHA's sepsis collaborative. Experts from all four care settings that the collaborative will initially focus on—pediatric and cardiac ICUs, the ED, hematology and oncology, and general care units—will be involved. "Most of the association's previous work has been in specific care settings," says Saffer. "Working across so many care settings is indeed very complex."

A challenge for the design team is determining "what kind of intervention can we work on that will be as uniform as possible across the care settings yet how can they be modified for those four care settings," Saffer notes. The team will also choose metrics, then conduct a yearlong pilot with 20 or more hospitals, and later bring in other hospitals.

Sepsis protocols themselves require a lot of intrahospital coordination. Transitioning patients to the ICU, performing other handovers, and "tracking exactly what stage of treatment that patient is at" are other elements that need to be coordinated, says Saffer.

Champions, Commitment, and Buy-In

A sepsis initiative will require leadership from individuals and commitment from providers throughout the hospital.

Hospital leaders need to understand the importance of improving sepsis recognition and treatment. "We're going to need very strong executive buy-in and executive participation," Saffer notes. Weingart states that risk managers can support the effort by educating leaders and other key stakeholders on what sepsis is and why it's important.

Identifying champions can further commitment. "You need to empower and fund a sepsis champion in the ICU and one in the ED. Task them with monitoring the outcomes of sepsis patients," says Weingart. "That investment will pay dividends . . . for your hospital's bottom line." The organization may also wish to assign a sepsis nurse, he suggests. In the STOP Sepsis Collaborative, "hospitals that demonstrated caring by actually creating a role for these people, those are the hospitals that excel," he states.

Clinicians can help spread the word. The CHA collaborative has the support of thought leaders and of governing groups at the association. "CHA improvement initiatives have always been led by clinicians," Saffer says. Citing the collaborative's team of more than 60 experts, she says, "Their reach out into their world of colleagues is huge."

Sharing results from the literature and improvement initiatives may also garner buy-in. Messineo suggests, "You need to discuss the literature" and show that the initiative is evidence-based. See the discussion

Quality Improvement for examples of how organizations use results of their initiatives to increase buy-in.

The goal is to send the message to providers: "There are very few things you can do that would make more impact on your patients than improving sepsis care," says Weingart. The benefit to patients is much greater than with stroke, for example; the impact on mortality risk can be "tremendous."

In addition, some are influenced by seeing the impact on individual patients. "You have to be able to show clinicians the personal story," says Messineo. She started reading Sepsis Alliance's "Faces of Sepsis" stories to nurses every day to give a personal perspective and show the challenges of postsepsis syndrome. "I wanted them to understand why it's so important to screen every patient."

Quality Improvement

The impact and complexity of sepsis make it a particularly good candidate for a formal quality improvement initiative. The CHA collaborative will collect data, on an ongoing basis, on how the interventions are being implemented and how reliably they are implemented, as well as outcomes. "We'll be looking frequently at what the performance looks like," Saffer explains, and adjusting the interventions if indicated. Fortunately, CHA has noticed, in the past decade or so, increases in "the level of expertise in improvement science and the ability of the hospitals to engage in quality improvement," she notes.

The involved hospitals will share lessons by communicating with each other constantly, through an online discussion group, webcasts, and face-to-face meetings. The collaborative will also involve "working with families, listening to families," says Saffer.

Presence Health also engages in ongoing review of sepsis data. It has a sepsis steering committee, which Messineo is a member of, that meets quarterly. Hospital-specific data includes compliance with the three- and six-hour bundles and mortality rates. The committee also reviews new research, screening tools, and order sets. Each individual hospital also has a local sepsis committee. It meets every month to examine individual cases, identifying opportunities for improvement.

Showing providers how many of the organization's patients are affected by sepsis and how the initiative is improving outcomes can also increase buy-in. Next to peer influence, "outcomes are typically what allow us to spread effective approaches," Saffer says. At Presence Health, "we worked very hard to develop a standardized sepsis screening process," Messineo says. "A turning point was when we evaluated monthly sepsis bundle compliance and mortality rates."

Once interventions are in place, sharing feedback with clinicians can further their commitment. "You absolutely have to have a structured reporting method because you need to give clinicians and departments feedback on how they're doing," says Messineo. "Seeing the data is what drives change."

Opportunity for Intervention

Sepsis presents major opportunities for intervention. It poses risks including high mortality, major liability concerns, massive costs for hospitals and patients, and reimbursement challenges. However, the involvement of risk management, quality improvement, and patient safety professionals can help overcome the obstacles to implementing and sustaining an initiative that has such wide-reaching impact and requires so much coordination. As Popp says, "We need to make sure every risk manager in the U.S. understands why sepsis is a critical risk management issue."