Patient violence and aggression is pervasive in healthcare settings and puts patients, staff, and the healthcare organization at risk.

Writing about patient violence, one physician remarked, "Sometimes the most dangerous thing in the hospital isn't the potential for medication mistakes, or medical errors—it's the patients." (Brewer)

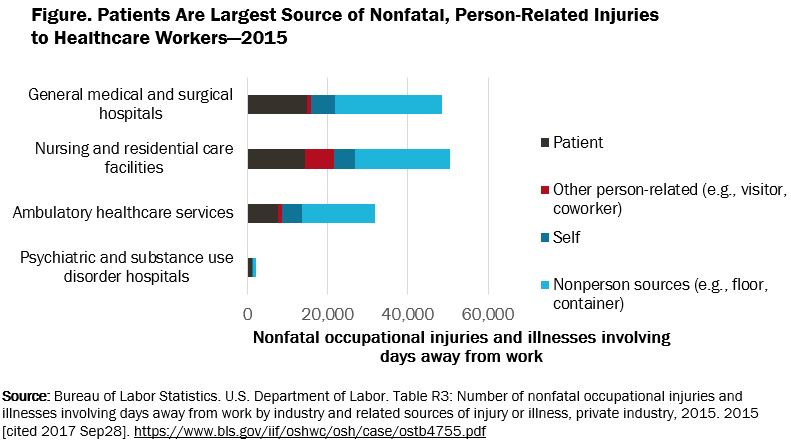

According to 2015 data from the U.S. Department of Labor, patients were the cause of 80% of all nonfatal occupational injuries to healthcare workers that involved another person and resulted in days away from work (BLS "Table R3"). Countless other verbal and physical assaults by patients are often not reported by healthcare workers, especially when the incident doesn't result in injury.

Event reports submitted to ECRI PSO show that doctors, nurses, ancillary staff, and security officers working in healthcare settings are greatly challenged in managing patients who become violent or threaten violence.

Consequently, in the five years (2014 -2018) that ECRI has compiled a list of the top 10 patient safety concerns confronting healthcare organizations, patient violence has made the list each year. The list has sometimes focused attention on patient violence by specifically addressing better management of the behavioral health needs of patients who exhibit psychiatric illness or emotional agitation during an acute-care stay.

Some of the many consequences from patient violence include:

- Injuries to healthcare workers and patients

- Low employee morale and job satisfaction

- Increased employee absenteeism and turnover

- Inadequate patient care because healthcare workers are distracted about their personal safety in the workplace

- Litigation, regulatory citations, and workers' compensation and disability claims against the organization

- Unwanted publicity about violent incidents, causing patients to avoid the organization

Risk managers can support their organizations in addressing the pervasive problem of patient violence and ensuring the safety and well-being of staff, patients, and visitors. OSHA and others have underscored the importance of a multipronged approach to curtail workplace violence. This guidance article describes such approaches, which include the following:

- Screening and identification of patients with the potential to commit violent acts

- Comprehensive training of staff to de-escalate agitated patient behavior to prevent the situation from developing into a crisis

- Availability of a trained, multidisciplinary team to respond to emergency calls when a patient's agitation intensifies and becomes too difficult for a caregiver or other staff member to manage

- Reporting and investigation of incidents of patient violence to identify strategies to prevent further violence

Although the information in this guidance article is specific to hospitalized patients, many of the recommendations also apply to nursing homes, where the number of resident assaults of staff resulting in injuries and days away from work are nearly double the rate of patient assaults on staff in hospitals (BLS "Table R8"). Staff who provide home care are also at risk for patient violence; refer to the guidance article

Home Care: Staff-Related Risks for more information.

Defining Patient Violence

Patient violence is a form of workplace violence, which also entails assaults by visitors, employees, and trespassers, as discussed in the guidance article

Violence in Healthcare Facilities. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) defines workplace violence as "violent acts (including physical assaults and threats of assaults) directed toward persons at work or on duty" (NIOSH). The agency and many other sources include verbal threats and threatening body language in the definition.

Besides affecting healthcare workers on the job, patient violence can also extend to other patients and individuals being treated in a healthcare facility. Patient violence as a result of self-harm is beyond the scope of this article; for more information on the topic, refer to the guidance article

Suicide Risk Assessment and Prevention in the Acute Care General Hospital Setting.

Patient violence can occur across the continuum of care, including during home care visits and in physician offices, hospitals, and continuing care facilities. Refer to

Examples of Workplace Violence Incidents Reported by Healthcare Workers for sample scenarios reported by healthcare workers interviewed by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) for a 2016 report on workplace violence in healthcare.

Scope of Patient Violence

When healthcare workers are injured at work, patient violence is often the cause. Overall, hospitalized acute-care patients were the source of 31% of all nonfatal occupational injuries to healthcare workers resulting in days away from work. Indeed, patients are the largest source of person-related injuries to healthcare workers as illustrated

in

Figure. Patients are Largest Source of Nonfatal, Person-Related Injuries to Healthcare Workers. Nonperson sources of the injuries include ground surfaces, furniture, containers, and vehicles. (BLS "Table R3")

|

More than likely, the data underestimate the extent of patient violence against healthcare workers for various reasons. First, employers' reports to OSHA about worker injuries and illnesses are sometimes incorrect (OSHA "Prevention"). Data from the reports are used in compiling information about healthcare worker injuries.

Second, numerous studies have found that episodes of workplace violence are underreported by healthcare workers, who may view the incidents as a "part of the job." For example, studies have found that only 30% of nurses report incidents of workplace violence. Among physicians, the reporting rate is 26%. (Phillips)

Risk Factors for Violence

Multiple factors can trigger patient violence. Although a patient's mental state is a key contributor, other factors unrelated to the patient may be involved.

Patient characteristics. The patient characteristics most common among perpetrators of violence are altered mental status associated with dementia, delirium, substance use disorder, intoxication, or deteriorating mental health (Phillips).

Healthcare workers cannot, however, rely solely on a patient's medical diagnosis as a predictor of violence. Certain situations may trigger patients to become agitated, such as long wait times, crowding, hunger, or being given bad news about a diagnosis or prognosis. Patients may also react violently to a needle or injection, pain, or discomfort (Arnetz et al.).

Setting. Sometimes, the environment sets the stage for patient violence. Within a hospital, patient violence can occur in any setting, but the areas most affected are EDs, which are open to the public 24/7 and can be busy and chaotic, and behavioral health units, where patients are more likely to have agitated behaviors (Phillips). Refer to

Hospital Areas at High Risk for Violence to identify areas within a hospital at greatest risk for violence.

Other environmental features of the setting can foster patient violence. Consider the following setting-related risks:

- Isolation of the healthcare worker from other staff while examining or treating a patient

- One-person workstations situated in remote locations

- Poor environmental design that may block employee vision or escape from an incident

- Poor lighting in hallways, corridors, and parking lots

Organizational risks. An organization's policies, or the lack of them, can also allow patient violence to arise. OSHA lists the following examples that put an organization at risk (OSHA "Guidelines"):

- Lack of facility policies and staff training to recognize and manage escalating hostile and assaultive behavior

- Low staffing levels at certain times, such as night shifts

- Inadequate security and behavioral health personnel on site

- Perception allowed that violence is tolerated and that victims will not report incidents

- Overemphasis on customer satisfaction over staff safety

Worker Safety

Nurses are among the group of healthcare workers receiving most patient assaults. One survey of nurses at a Florida hospital found that 100% of ED nurses reported verbal assaults and 82% reported physical assaults over a one-year period (May and Grubbs).

Nurses report that the most common form of verbal violence from patients is shouting and yelling and the most common types of physical violence are grabbing, scratching, and kicking. See

Table 1. Type of Violence Perpetrated by Patients against Nurses to see the extent of verbal and physical violence against nurses, based on a survey conducted at a mid-Atlantic health system.

Verbal Incidents |

Percentage of Nurses Experienced |

Physical Incidents |

Percentage of Nurses Experienced |

Shouting or yelling

| 60%

| Grabbing | 37.8%

|

Swearing or cursing

| 53.5%

| Kicking | 27.4%

|

Calling names | 43.4%

| Scratching | 27.4%

|

Ridiculing or humiliating | 25.9%

| Pinching | 25.9%

|

Threatening with physical assault | 27.3%

| Pushing or shoving | 20.9%

|

| | Spitting | 15.4%

|

| | Punching | 12.2%

|

Although less common, patients will also resort to other violent means, such as throwing food trays or furniture, using poles for intravenous medications to hit workers, and pushing a healthcare worker against a door. One incident, captured by a hospital's security camera, of a patient striking nurses at a nurses' station with a metal bar, went viral on mainstream and social media (Shocking Footage).

In comparison to other industries, nurses are the target of violence by another person at a much higher rate than other workers. In 2015, registered nurses were the victims of workplace assaults by another person leading to days away from work at a rate of 6.3 per 10,000 full-time workers, compared with a rate of 1.0 overall in private industry. (BLS "Table R100")

Other providers are also at risk of patient violence, including physicians, pharmacists, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurse aides, therapists, technicians, home healthcare workers, and emergency personnel. In 2015, workplace assaults among these groups ranged from 0.3 per 10,000 full-time physicians and surgeons to 236.9 per 10,100 full-time psychiatric technicians.

Beyond the immediate trauma of patients' verbal and physical assaults, consequences of patient violence toward healthcare staff include the following (Phillips):

- Burnout

- Decreased productivity

- Decreased sense of safety

- Increased absenteeism due to injuries or stress

- Job dissatisfaction

Patient violence can also lower employee morale and diminish a person's professional confidence. Some nurses leave the facility where they have been subjected to patient violence or leave the profession altogether (ENA). For example, one nurse recounted that she had to end her 20-year career as an ED nurse after a patient, who was also a professional boxer, slugged her, causing brain injury and multiple fractures. "This has been life-changing, and I feel let down by the system," she recounted (Jones).

Patient Safety

Worker and patient safety are inextricably linked. If workers feel unprotected and threatened, they are likely to make errors in patient care (NPSF).

A few studies have examined the impact of violent episodes on patient care. One study looked at the effect of violence on staff behavior toward their patients. The study found an association between staff experiences with violence and patient-rated quality of care and identified violence as a predictor of lower patient quality-of-care ratings (Arnetz and Arnetz). The study suggested that incidents of patient violence may interfere with staff members' ability to provide high-quality care.

Distractions, such as those resulting from workplace violence, can interfere with patient safety. Indeed, distractions are a common source of potential error (Feil), and one study found that workplace violence in 21 Australian hospitals was associated with increases in medication errors (Roche et al.).

There are also patient care risks for combative patients. Providers may avoid a patient who has a history of violence for fear that the patient will act out again. Some staff members may also avoid interactions with behavioral health patients because of the stigma associated with mental illness. Patient avoidance as a result of patient violence or a behavioral condition could negatively impact patient care by reducing staff's responsiveness to the patient's needs (Ideker et al.).

Patient-on-Patient Aggression

Patient violence can also jeopardize patient safety when a patient assaults another patient. Although most reports of patient violence in hospitals focus on harm to staff, there are cases of patient assaults by another patient, some of which can lead to injury. In one news report, a patient at a Canadian hospital experienced facial swelling and confusion after he was punched in the face by another patient staying in the next room. After the hospital called the injured patient's daughter to report the incident, the daughter called the police, who investigated the situation but took no further action. The hospital apologized for the incident and moved the daughter's father to another room farther away from the patient who had assaulted him. (Marchitelli)

Data about patient-on-patient assaults are sparse. Some studies have looked at resident aggression targeted at other residents in continuing-care settings, where these incidents are known to occur. In a study conducted over a two-week period at one long-term care facility, 2.4% of residents reported they were the victim of physical aggression by another resident, and 7.3% said another resident was verbally abusive (Hall). Most often, the victim was cognitively impaired and unknowingly wandered into another resident's personal space (Shinoda-Tagawa et al.).

Claims and Lawsuits

Patient violence can expose healthcare facilities to legal and regulatory risks. Courts have said that hospitals must have measures in place to protect those in the facility from harm. In 2004, for example, an Indiana court of appeals held that a hospital has a duty to take reasonable precautions to protect patients in its ED from violence. The court wrote, “There can be little dispute that a hospital's emergency room can be the scene of violent and criminal behavior. Violent and intoxicated individuals, those involved in crimes, and people injured in domestic disputes, are routinely brought to the emergency room for treatment. In some cases, the violence spills into the emergency room itself and measures must be taken to control the situation" (Lane v. St. Joseph's Reg'l Med. Ctr.).

Organizations may face employee-related costs as a result of patient violence. Although healthcare workers have not always been successful in the courts in collecting damages for injuries caused by patients, particularly if the patient is suffering from a cognitive condition that can impair judgment, employee injuries may be covered by workers' compensation laws, which can vary by state. One study found that the cost per case for assaults on registered nurses was $31,643. The costs include medical expenses, lost wages, legal fees, and other related costs (McGovern et al.).

In addition to workers' compensation costs, organizations may be responsible for disability claims for healthcare workers' injuries from patient violence. The organization may also encounter additional recruiting and training costs for finding staff to replace workers who are temporarily or permanently injured by violent patients.

An organization could also be held responsible for injuries to a patient involved in an altercation. A Louisiana jury awarded $700,000 to a plaintiff who sustained a broken leg and ribs when he assaulted several healthcare workers while being escorted from a hospital where he was being treated on a behavioral health unit. The patient had threatened staff and other patients during his stay, and the hospital decided to discharge him for failing to comply with its rules. The injuries occurred when a patient care technician tried to stop the patient, and both men fell to the ground. The hospital maintained that the technician was trying to protect nursing staff while escorting the patient from the hospital. The plaintiff claimed that the hospital failed to properly manage his condition to prevent his outburst. ("Mental Patient Attacked")

As addressed in the discussion

Regulations and Standards, healthcare facilities must adhere to state and federal requirements to provide a safe workplace environment and can be cited for regulatory deficiencies. In 2017, for example, OSHA proposed a fine of almost $208,000 against a Massachusetts behavioral health facility for continuing to expose workers to serious workplace violence hazards. OSHA originally issued a serious violation against the facility in 2015, which resulted in a formal settlement that included establishment of a workplace violence prevention program. OSHA opened a new investigation in early 2017 and found that the center failed to comply with multiple terms of the settlement. (OSHA "OSHA Investigation")

Besides incurring costs from patient violence as a result of litigation, regulatory citations, and workers' compensation and disability claims, organizations must confront the possible cost to their reputations. These costs can be difficult to measure, but they can have a far-reaching impact on operations. For example, an organization's known history for frequent patient violence can interfere with staff hiring and retention, thus increasing staff recruitment and training costs. Publicity about violence at a healthcare facility may also cause patients to avoid that facility, a cost that can be damaging to the facility operations (Rozovsky).

Several regulatory and accrediting agencies have guidelines that relate to preventing patient violence. In addition to the federal government, some states have specific requirements to address workplace violence. Risk managers should work with legal counsel to determine whether additional requirements—such as measures for patient privacy protections, involuntary hospitalization if a patient is a danger to himself or herself or others, or the forcible use of medications in emergency situations—apply in their facilities' jurisdictions and are appropriately reflected in the organization's policies and procedures for patient violence prevention and management.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

Healthcare facilities participating in the Medicare program must comply with Conditions of Participation (CoPs), which include a requirement that hospitals provide care in a safe setting (42 CFR § 482.13[c][2]) and that long-term care facilities maintain an environment free from hazards and risks (42 CFR § 483.25[h][1]). These CoPs have been interpreted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to include protecting patients and residents from harming themselves and others.

Failure to adhere to these requirements can jeopardize an organization's funding. In 2015, a Texas hospital was threatened with termination from the Medicare program when two off-duty police officers working as security guards at the hospital shot and wounded a patient who was having a panic attack and was delusional. CMS criticized the hospital for failing adequately train its security officers to respond to crises involving confused or aggressive patients. Under an agreement reached with the agency, the hospital was allowed to remain open while it addressed the agency's concerns about patient safety and quality of care at the hospital. (Hawryluk)

OSHA

There are no current federal regulations pertaining to any form of workplace violence; however, OSHA can cite healthcare facilities under its general-duty clause for failing to prevent patient violence against healthcare workers. Until 2011, when OSHA issued a directive for its inspectors on responding to complaints of workplace violence, the agency rarely cited healthcare facilities. The directive and the

updated 2017 version, identify healthcare facilities as high-risk settings for workplace violence. As a result, OSHA workplace violence inspections of healthcare facilities increased. From 2011 through 2015, OSHA inspected 107 hospitals and nursing and residential care facilities and issued 17 general-duty clause citations to healthcare employers for failing to address workplace violence. Most of the citations arose from employee complaints. (OSHA "Prevention")

OSHA can also issue a warning letter if an inspector identifies workplace violence hazards but finds that they do not meet all the criteria for a general-duty clause citation. From 2012 through May 2015, OSHA issued 48 Hazard Alert Letters to healthcare employers recommending actions to address factors that contribute to workplace violence. (GAO)

In its 2016 report on workplace violence in healthcare, GAO noted that OSHA does not have a process in place for inspectors to follow up with employers after issuing warning letters. In addition, the report noted that the agency provides insufficient guidance to its inspectors on developing citations under the general-duty clause for workplace violence hazards. GAO recommended that OSHA evaluate the need for a regulation addressing workplace violence in healthcare. (GAO)

In late 2016, OSHA began the regulatory process to consider a workplace violence standard, which would require healthcare employers to comply with measures to prevent workplace violence. After sidelining the rule in 2017, the Trump Administration signaled in 2018 that it continues to evaluate the need for the regulation by indicating that it is currently evaluating the impact that such a rule could have on small businesses. (Regulations.gov)

In place of regulation, OSHA issued guidelines in 1996, and most recently updated them in 2015, outlining a voluntary violence prevention program for healthcare facilities. OSHA's

Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence for Healthcare and Social Service Workers identifies healthcare settings as including hospitals, long-term care facilities, behavioral health centers and neighborhood clinics, group homes, and home settings where home healthcare workers visit. (OSHA "Guidelines")

In addition to addressing OSHA's guidelines on workplace violence prevention, healthcare facilities must also adhere to OSHA's recordkeeping requirements to report workplace injuries, including those that are the result of patient assaults. For more information on the requirements, refer to the guidance article

OSHA Illness and Injury Record-Keeping Standard.

State Oversight

Some states have their own OSHA-approved job safety plans giving the state oversight of employers instead of OSHA. Nine states with OSHA-approved plans specifically require healthcare employers to establish a plan or program to protect healthcare workers from violence. They are California, Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, and Washington. (GAO)

State requirements vary. For example, violence prevention regulations in New Jersey and Washington cover the healthcare sector broadly, whereas regulations in Maine are limited to hospitals.

California was the first state to require healthcare facilities to develop and maintain a violence prevention program. In 2016—more than two decades after California's law was passed in 1993—the state again adopted another first-of-its-kind state provision by requiring healthcare settings to have a written workplace violence prevention plan in place by April 2018. (Gunnin). The covered facilities must include employees in developing the plan. The rule, which went into effect in April 2017, applies to all health facilities in which individuals are admitted for a 24-hour stay or longer (Cal. Code Regs.).

Risk managers should be familiar with any state-specific requirements for workplace violence prevention that could affect their organizations' violence prevention program for patients.

Accreditation

Accrediting agencies require that organizations have measures in place to address patient violence. For example, the Joint Commission's environment of care accreditation standards require healthcare facilities to have a written plan to provide for the safety and security of patients, staff, and visitors (Joint Commission "Comprehensive"). The standards clearly support violence prevention programs by defining security risks to include workplace violence caused by individuals from inside or outside the facility. Among the requirements of the standard are the following: conduct a risk assessment to identify the potential for violence, provide interventions to prevent violence, and establish a response plan to use when incidents occur.

The accrediting agency identifies serious incidents of workplace violence (e.g., assault, rape, homicide) as a sentinel event. Because these incidents are consistently among the top 10 types of sentinel events reported to the agency, the Joint Commission issued a Sentinel Event Alert in 2010 on preventing violence in the healthcare setting and updated the Alert in 2017 with additional resources (Joint Commission “Preventing"). In 2018, the Joint Commission issued another Sentinel Event Alert, focusing on violence directed against healthcare workers by patients and visitors (Joint Commission "Physical and Verbal").

The 2018 Alert's recommendations to provide for the security of staff, patients, and visitors echo the principles of OSHA's workplace-violence prevention guidelines and include the following recommendations:

- Define workplace violence and put systems in place across the organization for staff to report workplace violence instances, including verbal abuse.

- Capture, track, and trend reports of workplace violence from multiple sources (e.g., complaints, employee surveys, OSHA reports, event reports), and include reports of verbal abuse and attempted assaults.

- Analyze workplace violence incidents to identify contributing factors, and identify priorities for intervention.

- Develop quality improvement initiatives (e.g., changes to physical environment, work practices, or administrative procedures) to reduce incidents of workplace violence,

- Train all staff, including security, in de-escalation and self-defense techniques and how to respond to a full spectrum of violent situations.

- Regularly evaluate the effectiveness of the organization's workplace violence reduction initiatives.

Restraints

In addition to adhering to any federal, state, and local requirements for workplace violence prevention programs, risk managers should review their organization's initiatives for violence prevention to ensure compliance with CMS and Joint Commission restraint requirements, which seek to limit use of restraints unless they are warranted or less restrictive interventions have failed to prevent serious injury or death. Facilities must balance the goal of achieving a restraint-free environment with the judicious application of restraints if staff and patient safety is compromised by an individual's violent and destructive behavior. For additional information, refer to the guidance article

Restraints.

Use "Building Blocks" for Violence Prevention

Action Recommendation: Obtain leadership commitment to workplace safety, and establish a culture that does not tolerate violent behavior.

Action Recommendation: Incorporate OSHA's "building blocks" for effective workplace violence prevention into the organization's approach to curbing patient violence.

Patient violence prevention is rooted in an effective workplace violence prevention program. OSHA's

Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence for Healthcare and Social Service Workers emphasize five elements that are the "building blocks" of an effective workplace violence prevention program in healthcare as follows:

- Management commitment and employee participation

- Worksite analysis and hazard identification

- Hazard prevention and control

- Staff training

- Program evaluation and improvement

Refer to the guidance article

Violence in Healthcare Facilities for information about incorporating these five elements into a workplace violence prevention program.

Each of the five elements should include provisions for preventing and addressing patient violence, as described below.

Management commitment and employee participation. Leadership support for a patient violence prevention program is key to the program's success. When organization leaders demonstrate their commitment to workplace safety and support a violence prevention program by allocating funds and resources to it, they help to create a culture that does not tolerate violent behavior.

At one health system, for example, the chief executive officer of each facility joins in a morning safety huddle at the facility to review incidents from the past 24 hours, which can include patient violence. (OSHA "Caring")

In such an environment, managers and staff are more likely to adhere to the organization's security procedures and protocols, devote time to staff training and preparedness, work as a team when incidents occur, and report all assaults and threats so the facility can use the information to identify improvements to its violence prevention program.

Worksite analysis and hazard identification. A worksite analysis of an organization's current practices can be used to identify strengths and weaknesses in a facility's efforts to prevent patient violence and to create a tailor-made plan for improvement. The analysis should include record review (e.g., event and security reports, workers' compensation claims, injury and illness reports), worksite security assessment, job hazard analysis, and employee and patient surveys.

OSHA provides examples of approaches used by some organizations in a

December 2015 resource to help healthcare employers establish a violence prevention program. For example, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) used the results from a national survey of its 70,000 employees, as well as other information sources, to identify its highest risk departments and occupations for assaults by patients. The survey findings also helped the agency recognize that the facilities committed to alternative dispute resolution training had lower rates of patient assaults. (OSHA "Caring")

Another health system used failure mode and effect analysis (FMEA) to proactively identify situations that made its staff more vulnerable to patient violence (refer to the guidance article

Failure Mode and Effects Analysis for more information about the FMEA process). After rating each identified failure mode based on its probability of occurring and severity of its effects, the system concluded that one potential failure mode that needed to be addressed was communication among staff from one care area to another and from shift to shift about patients at risk for violence. (OSHA "Caring")

Hazard prevention and control. Using its worksite analysis, an organization can take steps to address risks of patient violence with engineering controls and workplace adaptations (e.g., metal detectors to detect weapons, panic buttons, enclosed nurses' stations, accessible exit routes) and administrative and work practice controls (e.g., clear statement to patients, workers, and visitors that violence is not permitted; procedures for employees to report assaults; a trained team to respond to emergencies; communication to staff about patients with known history of violence). Refer to

Sample Engineering and Administrative Controls to Curb Patient Violence for examples. Some of these strategies are discussed elsewhere in the guidance article.

Each organization must decide on the best mix of controls to create a suitable atmosphere for providing care while ensuring that effective measures are in place to prevent violent incidents. For example, questions remain about the effectiveness of metal detectors in deterring workplace violence in hospitals. Facilities in areas where weapons are more commonly carried may prefer the installation of metal detectors, whereas other facilities may choose to invest their resources on controls more appropriate for them (Phillips).

OSHA also lists post-incident response and evaluation, as well as assistance to victims of violence as a component of hazard prevention and control. For more information, refer to the section

Establish Postevent Processes.

Staff training. Organizations should provide training for all staff on recognizing hazards, such as signs of potential patient aggression, and on following established policies and procedures to protect themselves and their coworkers. For more information, refer to the discussions

Train Staff and

Provide De-escalation Instruction.

Program evaluation and improvement. Organizations must establish systems to track and monitor patient violence through a variety of mechanisms, such as event reporting, worker injury logs, workers' compensation reports, documentation of hazard analyses and corrective actions, and records of staff training. Performance monitoring provides insights into the effectiveness of the patient violence prevention program and helps to identify the need for any improvements. For more information, refer to the discussion

Establish Postevent Processes.

Develop a Violence Prevention Program and Policy

Action Recommendation: Develop a comprehensive violence prevention program and policy that includes specific provisions for preventing patient violence.

Action Recommendation: Define patient violence to include verbal and physical threats and assaults.

An organization's violence prevention initiatives should be described in a written and comprehensive violence prevention program, which makes clear that preventing patient violence is part of the program.

Although some, including OSHA, have advocated a zero-tolerance approach to workplace violence, this approach could also undermine initiatives to encourage reporting of violent incidents. Staff may be afraid to report patient threats and violent episodes if such reports undercut the organization's implied goal to eliminate all violent episodes on the campus. Instead, staff must understand that the organization takes the issue of patient violence seriously, has provided measures to help staff manage threatening situations, and wants to know about incidents that occur.

Some healthcare system leaders have demonstrated their organization's commitment to violence prevention by sending a clear message to their patients that physical violence and threatening behavior are not tolerated. In the aftermath of a 2010 shooting at a Maryland medical center, the facility took stock of its approach to workplace violence and, among several initiatives, revised its patient and visitor handbook to state that unacceptable behavior, including physical violence and threatening behavior, can lead to discharge or restrictions on visits. Additionally, security staff meet with patients who have exhibited threatening or abusive behavior, even from a previous admission, and review the organization's expectations for appropriate behavior and the consequences for nonadherence. Some patients may be asked to sign a security contract acknowledging they are aware of the provisions for acceptable behavior and the consequences for failure to follow them. (Lessons)

At another hospital, senior leaders gave the go-ahead to notify patients who are repeat offenders of violence that they will not be permitted in the facility for treatment unless they require emergency care, as required by federal law. (OSHA "Caring")

Violence prevention policy. The organization's violence prevention policy provides the necessary guidance to implement its patient violence prevention program. The policy should accomplish the following:

- Define workplace violence to include both verbal and physical threats by patients as well as family members and visitors, and include examples of patient violence. The definition for workplace violence should be consistent with any applicable statutory definitions in the organization's jurisdiction. Broadening the definition of workplace violence to include verbal threats of violence or threatening behavior can prompt more frequent employee reporting of perceived potential for violence.

- Identify staff responsibilities for violence prevention, including staff obligations to attend violence prevention training and to promptly report any threats, including verbal attacks, and assaults by patients.

- Describe the organization's approach to investigate all reports of patient-initiated violent threats and incidents.

- Describe circumstances for reassigning a healthcare worker who is intentionally threatened or assaulted by a patient from caring for that patient and for requesting the presence of a second employee when caring for that particular patient.

The sample  Workplace Violence Prevention Plan combines the policy and program as a single document.

Workplace Violence Prevention Plan combines the policy and program as a single document.

Train Staff

Action Recommendation: Provide regular training and education of all employees and clinical staff on the organization's measures to prevent patient violence; assess staff competency in the techniques taught.

Action Recommendation: Address the training needs of security staff, including staff provided by outside agencies.

The organization must provide regular training and education of all employees—not just clinical staff—on the organization's measures to prevent patient violence and strategies to recognize and respond to potential and actual violent incidents. For example, registration staff may be among the first to encounter violent or potentially violent patients and should be prepared to respond. The training should also include staff on all shifts (including nights and weekends), medical staff,

locum tenens physicians, medical residents and interns, temporary or contract employees, and volunteers who could encounter aggressive patients. Attendance at the training program should be documented.

A Health System Risk Management member recently inquired about whether using Tasers on patients who are using an intravenous (IV) bag connected to an IV pump can cause any additional harm to the patient, beyond that intended by the Taser itself.

See our response.

|

Although staff training in the organization's violence prevention program is a component of OSHA's voluntary guidelines for preventing workplace violence, published evidence indicates an inconsistent approach to training, even in settings at high risk for patient violence. More than one in four nurses from a mid-Atlantic health system responding to a survey about workplace violence indicated that they had not received workplace violence training (Speroni et al.).

OSHA recommends that all new staff receive training in the organization's violence prevention program during orientation and that all staff receive refresher training at least annually (OSHA "Guidelines"). As part of any training, staff should also be asked to demonstrate their competency in using the techniques they have learned, such as self-defense strategies.

Staff working in high-risk settings, such as the ED, may need refresher training more frequently (e.g., monthly, quarterly). (OSHA “Guidelines"). Regular and repeated training can encourage sustained staff vigilance to prevent patient violence.

Organizations should also seek staff input on the adequacy of their violence prevention training. After surveying its staff about their attitudes related to safety, a New York hospital found that many of its staff members indicated that they were inadequately trained in recognizing signs of potential patient aggression and in de-escalating the situation (Ferguson and Leno-Gordon).

No single training program can address every worker's needs. Training should be customized to address the needs of different groups of healthcare personnel (e.g., nurses and other direct caregivers, ED staff, support staff, security personnel, supervisors, and managers). The Emergency Nurses Association, for example, provides a free, interactive

online course designed for ED nurses, managers, and staff. The unique training needs for security staff are discussed in

Security Staff Training. Direct caregivers can also benefit from training tailored to specific patient populations they serve (e.g., behavioral health, geriatric patients with dementia, ED patients) (OSHA "Caring").

OSHA's violence prevention guidelines suggest that topics to cover during training include the following (OSHA “Guidelines"):

- The organization's policies and procedures for preventing and managing patient violence

- Risk factors that cause or contribute to assaults (e.g., long waits, patient discomfort, crowded waiting areas)

- Warning signs of anxiety, both verbal and behavioral, that may signal volatile situations that could escalate into more disruptive behavior

- Methods to diffuse a patient's anxiety before it escalates into a crisis

- Procedures to enact the organization's response plan if the patient starts acting out and becomes violent

- Techniques for personal protection, including self-defense procedures and use of a buddy system

- Procedures for reporting patient threats and violent events

- Resources available for victims of workplace violence, including patient violence

Although an organization may benefit from having outside experts conduct or oversee the training, there is no federal requirement that it be done this way. Regardless of who conducts the training, those responsible for identifying the content of the training program should ensure that it covers topics such as those listed by OSHA, as well as organization-specific issues.

A

web-based workplace violence prevention training program for nurses, covering many of the training topics suggested by OSHA, is available online at no charge from NIOSH. It has 13 modules, and each takes about 15 minutes to complete. Although organizations will want to tailor their violence prevention training to their specific needs, they may choose to supplement their program with some of NIOSH's material. (NIOSH "Workplace Violence")

The organization should also conduct drills, engaging actors to pose as disruptive patients, so staff from all shifts can test the skills they have learned from violence prevention training. The drills can help to identify any deficiencies in the organization's response plan, such as defective panic buttons and alarms.

Security Staff Training

Security staff, including personnel provided by outside agencies, should receive specialized training about the healthcare environment and the organization's workplace violence prevention program. Some hospital security staff have previous training as police officers or in the military and are unfamiliar with managing the needs of patients, particularly those with a behavioral health condition or some form of cognitive impairment. For some agitated patients, just the presence of a security officer can increase their anxiety. Also, as discussed in Regulations and Standards, a Texas hospital was threatened with termination from the Medicare program for its failure to adequately train two off-duty police officers working as security guards who shot and wounded a patient who was having a panic attack and was delusional.

Training can address the organization's expectations, as outlined in its violence prevention program and policies, of its security personnel and methods to diffuse hostile situations. Depending on their assignment to treatment settings, security staff may need additiona l training for the particular setting where they work, such as the ED, behavioral health units, and memory units for individuals with dementia, Alzheimer disease, or other forms of cognitive impairment.

Some security staff may have previous experience dealing with violent behavior (for example, as a former police officer) or may possess certification from groups such as the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety; how ever, neither experience nor credentials should be viewed as criteria to exempt an individual from training that addresses the organization-specific issues and policies and procedures. Training is essential for individuals to be competent to perform their jobs in the particular setting where they work.

Provide De-escalation Instruction

Action Recommendation: Provide staff with guidance on recognizing verbal and behavioral cues that suggest a patient could become combative and on techniques for managing these patients to avert a crisis.

Action Recommendation: Educate staff on appropriate and inappropriate techniques to handle aggressive behaviors.

No training program can cover every scenario that could arise with threatening patients. But training can empower staff with the appropriate set of responses for patients who show signs of agitation and with the necessary procedures to follow if the situation escalates.

Therefore, an important component of staff training in violence prevention is to educate staff to recognize the verbal and nonverbal cues that suggest a patient could become combative. Training should also provide strategies for managing the situation before it escalates into a crisis and requires activation of the organization's violent incident response team or the use of more forceful measures, such as restraints. Unfortunately, many training programs are deficient in educating staff in de-escalation techniques and in techniques for redirecting patients who are starting to show signs of aggression.

- Argumentative

Clenched fists Hyperalert state Less responsive to redirection Physiological signs (e.g., dilated pupils, sweating, flushed skin, facial grimaces, breathing changes) Refusing medications Somatic complaints Withdrawal or isolation

|

Most violent behavior is preceded by verbal and nonverbal warning signs. Educating staff about these warning signs and about appropriate approaches for managing the patient can prevent the situation from escalating into a crisis. Refer to

Verbal and Nonverbal Signs of Escalating Aggression for examples of warning signs.

Of course, staff should also consider whether any signs of agitation or anxiety have a physiologic basis requiring medical intervention. For example, untreated urinary tract infections in the elderly are sometimes confused with cognitive disorders because the patients can exhibit symptoms of confusion, agitation, and other behavioral changes. Once the condition is treated with antibiotics, the behavior often stops.

Staff members who are confronted with signs of patient agitation need to know how to deal with the individual. Staff should be aware how their attitudes and reactions toward a patient can either escalate or de-escalate a situation. By remaining calm and by listening to the patient and using an open and accepting approach, staff can diffuse the situation. Conversely, telling a person to calm down or that the individual has nothing to be upset about is ineffective and could, in fact, trigger more agitated behavior.

De-escalation skills should be reviewed during the organization's training in violence prevention. Role playing and simulation are effective methods for staff to apply what they have learned. Other de-escalation techniques that could be discussed during training are:

- Be empathic and open; do not judge the patient.

- Respect an individual's personal space; stand 1.5 to 3 feet away from the patient.

- Maintain nonthreatening nonverbal communication; be mindful of gestures, facial expressions, and tone of voice.

- Remain calm and professional; avoid overreacting.

- Listen to the individual; validate the patient's feelings.

- Avoid engaging in a power struggle; if the patient challenges your authority, redirect their attention to the more immediate concern.

- Set limits; offer clear and concise choices and consequences.

- Know which rules are negotiable and which are not; do not promise something that you cannot deliver.

- Allow time for reflection; let silent moments occur for the patient to reflect on what is happening.

- Avoid rushing; give the patient an opportunity to think about what you are saying. (Eilers)

Sometimes a patient's abusive behavior is the result of service issues that are unaddressed, such as long waits in the ED or a repeatedly slow response by the unit staff when a patient activates a nurse call bell. After identifying customer service issues as the source of some problem patient behavior, one hospital started a clinical customer service program for each of its care units. A customer service team is available to promptly address patients' grievances in real time. For more information, refer to the guidance article

Managing Patient Complaints and Grievances. (Lessons)

Assess Patients for Potential Violent Behavior

Action Recommendation: Adopt a process to identify on admission patients who have the potential to become violent.

Action Recommendation: Communicate the patient's risk of developing aggressive behavior to staff who come into contact with the patient.

Studies have found that patients involved in violent incidents tend to be older and male. The data provides insights into some perpetrators of violence, but not all. Healthcare organizations should, therefore, develop a process to identify patients on admission who have the potential to become violent based on common risk factors for violence, such as a history of violence, suspected substance use disorder, and cognitive impairment.

Some hospitals may also choose to reassess patients periodically after admission. One hospital, for example, assesses a patient for potential violence risk upon admission and every 12 hours thereafter. (OSHA "Caring")

An assessment tool, called the M55 form, prompts caregivers to flag individuals' charts if their histories or current conditions include certain risk factors, such as a history of violence or signs of intoxication (Kling et al.). Another tool, called the Aggressive Behaviour Risk Assessment Tool, uses elements of the M55 form and other predictors of violent behavior to identify potentially violent patients in medical-surgical units (Kim et al.). Because it excludes patients showing signs of intoxication or substance use, it is inappropriate for the ED setting. The elements of the tools are listed in

Table 2. Sample Assessment Methods to Identify Acute-Care Patients at Risk for Violent Behavior. Behavioral health units and facilities may require tools that are more specific to patients with psychiatric disorders (Kim et al.).

|

M55 Form* | |

Aggressive Behavior Risk Assessment Tool** |

Presence of any one of the following: - History of violence or physical aggression

- Physically aggressive or threatening behavior

- Verbally hostile or threatening behavior

| Patient displays three or more of the following behaviors: - Shouting or demanding

- Displaying signs of drug or alcohol intoxication

- Suffering auditory or visual hallucinations

- Threatening to leave

- Being confused or cognitively impaired

- Being suspicious

- Being withdrawn

- Being agitated

| A patient's risk of becoming violent is scored based on the presence of any item from the list. A score of zero indicates a low risk of becoming violent, a score of one indicates a medium risk, and a score of two or higher indicates a high risk. - Confusion or cognitive impairment

- Anxiety

- Agitation

- Shouting or demanding

- History of physical aggression

- Threatening to leave

- Physically aggressive or threatening behavior

- History or signs/symptoms of mania

- Staring

- Mumbling

|

Other assessment tools used to screen for behavioral and substance use disorders may also be helpful in identifying patients at risk for violence. Refer to

Additional Resources to access those tools.

Recognize, however, that assessment tools cannot correctly predict every violent incident, and the tools must be used along with ongoing education on violence and aggression prevention and de-escalation. (Kling et al.)

Indeed, staff must be empowered to think critically about changes in a patient's situation, condition, and environment that could provoke a patient who is otherwise at low risk of violent behavior. In particular, changes in a patient's medications may contribute to behavior changes, and staff should examine new medication orders that could provoke such changes. Additionally, staff should initiate medication reconciliation of any newly admitted patients, including those admitted from other units within the hospital. For example, a postsurgical patient may need to resume taking prescribed psychiatric medications that the patient had to discontinue taking just before surgery; failure to resume the patient's medications could provoke violent behavior that the patient could otherwise control (for more information on managing acute-care patients with behavioral health issues, refer to

Address Patients Behavioral Health Needs).

Communicating Patient's Risk of Violence

An ECRI member recently asked

for information about creating a hospital policy on terminating relationships with patients.

See our response. |

Information about the patient's risk for violence must be communicated to staff who need to know such information. The information should be communicated respectfully to help staff appropriately manage the patient but without deterring interactions between caregivers and patients. Some organizations flag an individual's medical record to indicate to staff that the patient may be predisposed to violent behavior. Such measures, used by VHA, have prevented aggressive behavior from recurring among patients with a history of violence (Phillips). If the organization maintains electronic records, an audible alert could also be used to warn staff.

One hospital uses multiple methods to warn staff of patients at risk of violence. In addition to flags in the medical records, the hospital also warns staff by posting gray signs on a patient's hospital room door and by giving a patient a gray hospital gown to wear. Staff are aware of the significance of the gray sign and gown. Another organization has configured its information technology system to scan the daily census data and to generate an email to key staff if any of the admitted patients have a previous history of violence against staff. (OSHA "Caring")

During handoffs, communication about a patient's risk for violence must be approached with the same level of seriousness as communication about other patient matters, such as fall risk or the presence of an infection requiring the need for contact precautions. Transporters and ancillary staff, who have only intermittent contact with the patient and may be unaware of information about the patient in the medical record, must be informed of the patient's risk for violence.

Patient Privacy

Privacy rules issued under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) generally prevent disclosure of patients' protected health information (PHI) to individuals who do not need it for treatment, payment, or healthcare operations without obtaining the patient's written authorization. However, significant concerns over patient violence and staff safety may fall into an exception that permits disclosure (45 CFR § 164.512[j]) of PHI without the patient's authorization. Covered entities under HIPAA may disclose PHI that they believe is necessary to prevent or lessen a serious and imminent threat to a person or the public when such disclosure is made to someone they believe can prevent or lessen the threat (which may include the target of the threat). Covered entities may also disclose PHI to law enforcement if the information is needed to identify or apprehend an individual who participated in a violent crime that caused serious physical harm to the victim. Thus, clinical staff may notify anyone who could be affected by a violent patient about a serious and imminent threat. These individuals would include a security guard, receptionist, or transporter who comes into contact with the patient. Such disclosures should contain only the minimum amount of information necessary to adequately warn those who could be affected by the potential violence.

Nevertheless, facilities considering a process to flag patients at risk for violent behavior should discuss possible HIPAA privacy rule implications with their privacy and security officers, legal counsel, or other appropriate individuals and have the necessary policies and procedures in place to ensure appropriate disclosure of the information. In jurisdictions where state privacy rules are more stringent than HIPAA rules, the stricter rule applies. For more information on the federal rule, refer to the guidance article

The HIPAA Privacy Rule. Given that some patients at risk for violence have behavioral health issues, risk managers should also refer to the

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' guidance about when it is appropriate under the privacy rule for a healthcare provider to share the protected behavioral health information of a patient.

Risk managers should seek legal counsel regarding state privacy rules that must be observed, as well as other pertinent state and federal laws that could affect the organization's approach to identifying and managing patients at risk for violence. For example, are there any state statutes addressing the organization's or its providers' obligations to notify others of a patient's potential violence toward others? (For more information, refer to the guidance article

Duty to Warn or Protect.) Additionally, legal counsel can provide guidance on other avenues that may be under consideration to identify at-risk patients, such as information that the patient has made publicly available on social media (refer to the guidance article

Social Media in Healthcare for more information).

Address Patients' Behavioral Health Needs

Action Recommendation: Address the behavioral health needs of patients hospitalized with a medical condition by providing access to behavioral health professionals.

Action Recommendation: Enlist pharmacy department support to appropriately manage behavioral health patients' medications.

Action Recommendation: Ensure an adequate supply of psychiatric medications is available on medical units.

About one out of every three hospitalized adult patients has behavioral or substance-use disorders that are intertwined with their hospital admission for a medical condition (Heslin et al). Patient safety events submitted to ECRI Institute PSO often underscore the challenges for healthcare staff in simultaneously managing a patient's medical needs along with the patient's behavioral condition, which, for a variety of reasons, can sometimes cause a patient to become unruly and disruptive, escalating beyond a staff member's ability to control.

Staff, who are expecting to treat medical conditions, must also manage the patient's mental state, yet may not have the necessary training. Further, staff may sometimes be unaware that a patient with behavioral health issues requires psychiatric medications if the information is not available at admission or not visibly noted in the medical record. The patient may begin to experience symptoms during the hospital stay which staff are either uncomfortable with or unfamiliar with managing. Before long, the patient's behavior becomes increasingly difficult to manage.

ECRI Institute recommends a variety of system-based solutions to help staff manage behavioral health patients, as listed below.

Multidisciplinary approach. Caring for individuals with a combination of behavioral and medical conditions requires a multidisciplinary approach, involving clinicians, caregivers, pharmacy, behavioral health professionals, social services, and others.

If a hospital operates a behavioral health unit, it can also provide staff on medical units with access to their behavioral health teams (refer to

Behavioral Health Resource Teams for an example of one hospital's approach).

At Indiana University Health Bloomington Hospital, staff on the medical units can call its behavioral health resource team for help assessing and handling patients who are displaying difficult behaviors, such as acting aggressively. There is at least one member from the team available at any time. When a team member is called to assist with a patient, they will also meet with the patient's nurse and offer suggestions to help manage the particular patient. Rather than taking over the patient's behavioral care needs, team members empower and educate staff in dealing with challenging patients. Since implementing the team in 2005, the hospital has been able to decrease the number of escalating events requiring the involvement of security and increase nursing staff's comfort level in managing the patients. |

Pharmacy department support. Given the possibility that some medications or a combination of medications may affect patient behavior in undesired ways, caregivers should enlist their pharmacy departments to provide guidance on medications' effect on behavior, as well as possible drug interactions and contraindications. Pharmacists should work closely with nursing staff to ensure that patients' medication schedules are closely monitored to prevent any interruptions in administering the patients' psychiatric medications, particularly during transitions of care. For example, patients with substance use disorders can experience withdrawal symptoms, which can trigger aggressive behavior, when medications to manage their withdrawal are omitted from their medication orders.

The pharmacy departments should also regularly check medication supplies on the unit to confirm availability of necessary medications to manage emergency psychiatric conditions. To ensure that the medication inventory is adequately maintained, the pharmacy department should monitor units' medication usage reports to check that medication supplies for psychiatric conditions do not dip below a predetermined level based on the unit's typical usage rate.

Telepsychiatry. Not all healthcare facilities have access to behavioral health professionals on the facility premises. Some hospitals have identified a role for telemedicine to facilitate electronic behavioral health consultations between patients and behavioral health specialists able to “visit" with the patient from a remote location. Although the patient and behavioral health professional may not be in the same room, the visit can still be one-on-one with videoconferencing technology.

The South Carolina Department of Mental Health and the South Carolina Hospital Association received funding to establish a statewide telepsychiatry network serving all hospitals with EDs in the state. ED clinicians have 24-hour access to the network's psychiatrists and psychiatric residents who can provide psychiatric assessments, prescribe medications, and initiate treatment as needed. Previously, patients could wait two to three days before being assessed by a behavioral health professional. As of May 2015, the average wait time for an assessment had decreased to 8.5 hours. (SC DMH)

Telepsychiatry has significant barriers that can affect its implementation and use. Obstacles include costs, licensing, credentialing, privileging, privacy and security protections, and the liability aspects of providing medical opinions and care to patients who a practitioner does not see face-to-face. For more information, refer to the guidance article

Telehealth.

Standardized protocols. Nurses on the medical unit should have access to standardized nursing and medication protocols for managing substance use disorders and various psychiatric conditions. For example, patients with behavioral health conditions could be placed in a room that can be seen from the nurse's station for close monitoring of the patient and interactions with staff and visitors. Protocols might also call for closer monitoring of the patient during meal times and shift changes, when disruptive behavior can increase.

Family engagement. With most patients, family members know the patient best. If the patient is prone to anxiety, for example, family members can provide input about their loved one's needs (including information about any psychiatric medications taken by the patient) and explain what can trigger a change in the patient's behavior. Family members may also know the best approaches to help calm that patient.

Patients should be encouraged to identify as support persons the individuals whose opinions about their healthcare is valued and whose involvement they believe would be helpful. For example, by engaging the patient and a designated support person, whenever possible, in bedside change-of-shift reports, the patient or support person may become aware of psychiatric medications that were omitted from the patient's usual drug regimen. Listening to staff members' discussion about the patient's care, the patient or support person may be able to identify situations that could increase the patient's anxiety. Or, by providing patients and an authorized support person with open access to their medical records, they may identify errors in their medication orders, such as psychiatric drug omissions.

Manage Risks in ED Environment

Action Recommendation: Minimize anxiety-producing stimuli in the ED environment, where the risk for patient violence is high.

Action Recommendation: Ensure protocols are in place to manage individuals in police custody or prisoners in need of medical care who are brought to the facility.

Even though it is often the hospital entry point for patients, the ED can be poorly suited for patients at risk for aggression. ED crowding, insufficient space, long waits for assessment, and the presence of security staff monitoring the patient are all factors that can cause the patient to become agitated and anxious. What might have been a successful encounter can quickly turn into a confrontation between the patient and caregivers with the patient refusing to cooperate due to the influence of environmental stimuli. Some measures that may increase the likelihood of a successful outcome in the ED include the following:

- Ensure that the initial evaluation of a patient with an apparent behavioral health issue involves an investigation into possible medical causes contributing to the patient's behavior.

- Foster staff sensitivity to the needs of the patient despite, for example, staff's possible frustration with a patient with a substance use disorder who is frequently treated in the organization's ED.

- Minimize the duration of the patient's wait to be assessed and evaluated.

- Create a waiting area that is comfortable and safe for everyone and designed to minimize stress (e.g., sufficient seating and space, adequate room temperature, no unnecessary noise).

- Move a patient who is showing signs of agitation to a quiet area, away from the bustle of the ED patients.

- Ensure that a patient at risk of outbursts is supervised, while balancing the patient's need for privacy. Some facilities have set up dedicated space for patients with psychiatric emergencies where staff can observe the entire area from a central location.

- Educate all ED staff, including security personnel, on interacting with people at risk for violence.

Special attention must be given to ensuring protocols are in place to manage individuals in police custody or prisoners in need of medical care who are brought to the facility. Consider the following incident at a suburban acute care facility. A police suspect brought to the facility's ED for blood alcohol testing stole a police officer's gun, shot and injured one officer and a healthcare worker and shot and killed a second officer. The patient was handcuffed when he was brought to the hospital, but the handcuffs were removed when he went into the bathroom to give a urine sample. He took the officer's gun when he exited the restroom. (Ciavaglia "Hospitals")

After the incident, the facility converted an ambulance squad room into a dedicated room for managing police suspects who are brought to the hospital ED for testing. The room was designed to eliminate contact between police suspects and the general public and to ensure that individuals in police custody remain closely guarded. (Ciavaglia "St. Mary") For additional information, refer to the guidance article

Hospital Relations with Police.

Provide Rapid Response Teams

Action Recommendation: Establish an interdisciplinary response team trained to handle combative patients.

Action Recommendation: Develop a process for staff to activate a code to mobilize the response team to help with a difficult patient.

If a patient starts to show signs of loss of control, staff must be prepared to remove themselves and others in the area from the situation and to activate the organization's procedure for immediate response to potentially violent behavior. The notification system should use redundant processes, such as a combination of activating panic buttons and overhead code alerts, in case one of the measures fails.

Some hospitals have developed rapid response teams whose purpose is to provide assistance with patients and others who become disruptive and pose a threat to themselves and others. Although there are various names for these teams, a frequently used term is "behavioral emergency response team." A Minnesota hospital reported that the rapid response teams not only helped improve the management of behavioral emergency situations but also contributed to enhanced staff satisfaction (Pestka et al.)

Rapid response team members consist of individuals within the organization selected and trained to interact with combative patients. At one hospital, for example, the interdisciplinary team of responders consists of inpatient nursing staff, clinical administrators, inpatient therapists, psychiatrists, and security staff. The team is activated when there is an overhead “code gray" alert. (Ferguson and Leno-Gordon)

Besides conducting debriefings after each event, the team schedules monthly meetings to discuss difficult cases and review performance data related to crisis interventions. The team also conducts drills to practice their response to mock events and to identify any areas for improvement in their response. (Ferguson and Leno-Gordon)

Team members may be called upon to apply restraints or to assist with forcibly medicating the patient. Risk managers must provide guidance in advance to team members on applicable state and federal laws on the use of restraints and forcible medication (for more information, refer to the guidance article

Refusal of Emergency Psychiatric Treatment).

Establish Postevent Processes

Action Recommendation: Establish a process for managing events of patient violence, and ensure that staff understand the importance of reporting events, both threats and actual assaults.

Action Recommendation: Use debriefings after every event so that those involved in the event can reflect upon the experience, discuss what went well, and identify opportunities for improvement.

A member asked whether a facility should create a record of treatment when patients or visitors are seen for treatment of injuries sustained while in the facility.

See our response. |

Incidents of patient violence should be managed like most adverse events. The immediate focus is to care for anyone who has been injured. If criminal prosecution is possible or police were called to the scene, the risk manager and other designated leaders from the facility must simultaneously coordinate with law enforcement officials who will want to conduct their own investigation of the incident. Once the incident's immediate aftermath is addressed, the organization must follow its policies to document and investigate the event, as well as to offer any counseling and emotional support for staff affected by the incident.

ECRI recommends using debriefings after every event so that those involved in the event can reflect upon the experience, discuss what went well, and identify opportunities for improvement. Refer to

Debriefing Questions After Incidents of Patient Violence for suggested questions to prompt discussion about the event. The debriefing is an important learning opportunity for staff as they address their concerns about the event and discuss what did and did not work well in managing the patient.

Based on information learned from the debriefing and event investigation, the organization should consider the need for additional training to address any identified gaps or concerns.

- Was the expected outcome achieved by using the least restrictive intervention? If not, why?

- Were the patient's dignity, rights, and safety maintained at all times?

- Were enough staff available to control the incident?

- Was there an interaction between a patient and a staff member that required intervention by another staff member?

- Did staff involved intervene appropriately using therapeutic techniques?

- Are there any aspects to the staff response that require improvement or alternative solutions?

|

Underreporting by staff of violent incidents and threats is a pervasive problem in healthcare facilities that must be addressed. In its review of recent studies on the reporting of workplace violence incidents in healthcare, GAO found that the percentages of cases formally reported ranged from 7% to 42% (GAO).

Among the reasons staff give for not reporting are the following (GAO; Phillips):

- Belief that reporting is only needed if the worker sustains injuries

- Burdensome reporting procedures

- Perception that violence comes with the job

- Fear of being blamed for causing the attack

- Belief that some patient cannot be held accountable for their violent actions because of their behavioral or physical condition

Risk managers should work with their organizations to remove these impediments to reporting. Healthcare workers must understand that their incident reports of violent threats and assaults are taken seriously by the organization and acted upon in a timely fashion. During training sessions on the organization's violence prevention program, staff should be reminded of the importance of reporting and should be provided with examples of incidents—ranging from verbal threats to physical assaults—that are reportable. Examples can be given of how the organization followed up after a reported incident, such as by making a change in a protocol.

The organization's violence prevention policy should clearly define the types of incidents that are reportable so that staff do not wrongly assume that reporting is limited to incidents that result in injury. Additionally, the organization's policy should make clear that the facility does not retaliate against workers for reporting incidents of violence. Making reporting systems easy to access and use can also encourage more reporting.

Some experts contend that an intense focus on customer service in healthcare deters staff from reporting patient violence (Phillips). Risk managers should be aware of this complaint and assess whether the mentality that "the customer is always right" is a barrier for reporting in their organizations and whether more visible leadership support for preventing patient violence is needed.

Those involved in the incident should be included in the event investigation because they can help to identify the issues that contributed to the incident and contribute to pinpointing strategies to prevent future incidents. Staff, particularly those who reported an event, should receive feedback on the anticipated actions to prevent further violence.

Other risk management considerations for the organization's postevent response include the following:

- Providing counseling and support to the victims and other staff affected by the violent incident. The organization's employee assistance program may be able to provide help for affected staff, or the organization may determine that additional support and counseling is needed. Some individuals may not immediately show symptoms from the incident, so risk managers should ensure ongoing availability of support for affected staff.

- Offering, if appropriate, to separate a staff member who was assaulted by a patient from any continued involvement with the patient or providing other means, such as a buddy system, to ensure the staff member's confidence in providing patient care.

- Determining whether the incident resulted in an injury reportable to OSHA and if so, completing the OSHA injury and illness incident report and the log of work-related injuries and illnesses within the required time frame (for more information, refer to the guidance article

OSHA Illness and Injury Record-Keeping Standard).

- Providing guidance on the applicability of workers' compensation and disability benefits for a work-related injury or disability from a violent incident (for more information, refer to the guidance article

Workers' Compensation).

Finally, as part of its overall violence prevention program, organizations should have a process in place to monitor the program's effectiveness, including newly implemented corrective actions after an event, and to continually look for any deficiencies in the program that should be addressed. Senior leaders should be presented with data (e.g., rates of worker injuries caused by violence, workers' compensation claims) to evaluate the program and, if necessary, to target additional resources to the program. Management should also share its evaluation of the workplace violence prevention program with its staff and keep them apprised of any successes or needed changes.