Over the past year, there has been growing concern that patients infected with the Ebola virus might appear in U.S. hospitals. This concern was validated in late September 2014 when Thomas Duncan arrived at the emergency department at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas, Texas, and was later admitted after being diagnosed with Ebola virus disease (EVD). He subsequently died of the disease while in the hospital. Despite the hospital having an Ebola response plan that included using recommended personal protective equipment (PPE), two nurses involved with Duncan's treatment contracted EVD. These events not only made it clear that an EVD patient could arrive at any hospital, but also raised concerns that hospitals might not have the appropriate PPE and medical equipment available to treat such patients safely.

In the wake of the September events, ECRI Institute began getting questions about PPE and medical equipment from hospitals. In November, we surveyed hospitals to assess the status of their Ebola preparedness planning and to learn what challenges they have encountered in selecting PPE and other equipment and supplies that might be needed to treat an EVD patient. We were pleased to have received nearly 450 responses to the survey.

Here is a summary of the survey responses. We've also added commentary on some of the more notable findings and issues. Most questions offered multiple-choice replies; many questions also included an "Other" category in which respondents could write their own answers. Also, a few questions allowed more than one answer.

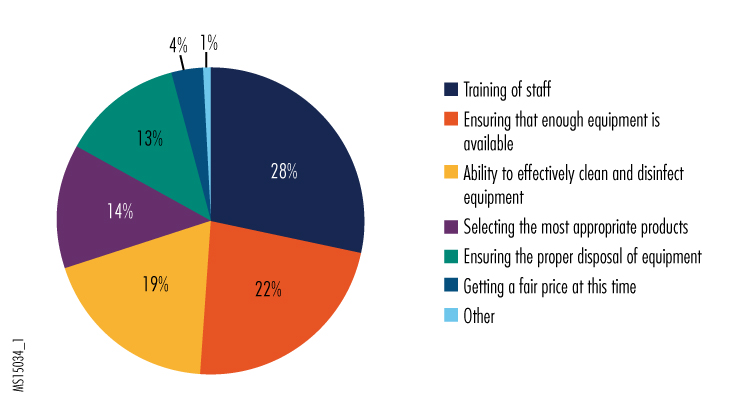

1. What are your most pressing equipment/technology concerns in managing patients with Ebola or other very high-risk infectious diseases?

Among the "other" responses, participants reported that equipment was on back order, that they had concerns about being able to properly isolate EVD patients or equipment used on EVD patients, and that they had concerns about being able to get staff to comply with the recommended equipment-use training and to adhere to protocols and procedures.

We were interested to note that concerns about training staff in the proper use of equipment was the leading answer; based on the "other" responses, we believe this likely reflects staff's concerns about challenges in using PPE correctly.

The severity of PPE shortages being reported by respondents was something that we had not anticipated. But as this National Public Radio news story outlines, PPE manufacturers have been overwhelmed not only by demand in the United States, but also by the enormous consumption of such equipment in West Africa, where clinics reportedly go through hundreds of sets of PPE daily. Reassuringly, manufacturers are ramping up production and expect to be able to meet demand soon.

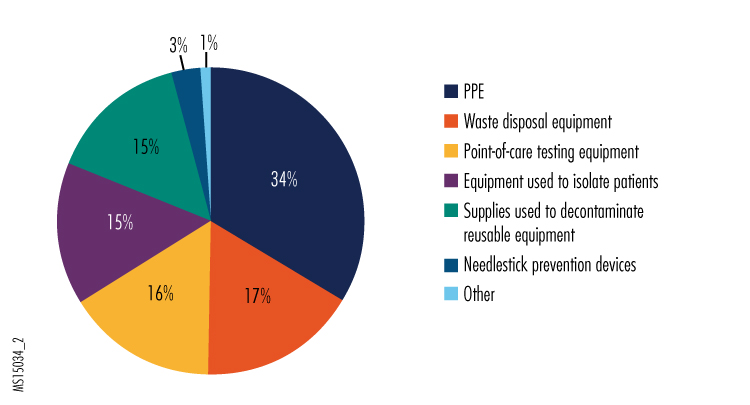

2. Please indicate what equipment presents the greatest selection and use challenges in your organization's preparedness planning for Ebola and other high-risk infectious diseases.

Given the reports of PPE shortages and concerns about getting staff properly trained in its use, we weren't entirely surprised that selection and use of PPE was the leading answer to this question.

Based on some of the "other" responses, we believe that part of the difficulty in selecting PPE is deciding what level of recommended protection is necessary for clinical staff. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends either the use of an N-95 respirator with face shield and hood, or the use of a powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR). Although the Ebola virus is not considered to be an airborne infection hazard, some infection control experts have raised concerns that aerosols generated during some clinical procedures could put staff in jeopardy, so many hospitals are selecting the more protective (and expensive) PAPRs. Both types of respirators require training for use. N-95 respirator masks can be challenging to use for people with facial hair and require fit testing to ensure that they provide maximum protection for all wearers. This higher level of effort required for safe use might also be driving hospitals to select PAPRs.

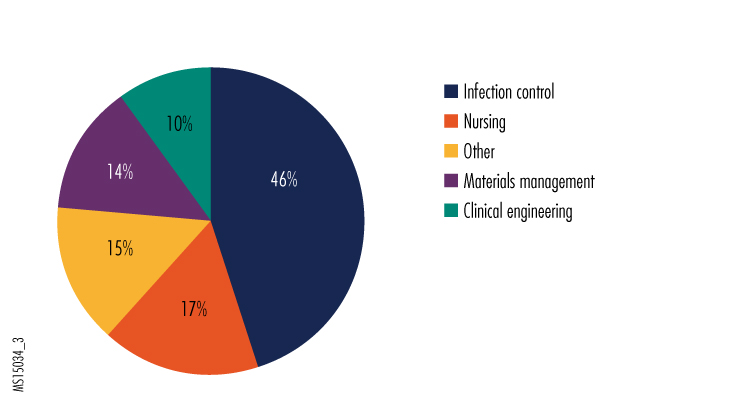

3. Which department is in charge of equipment/technology matters regarding your organization's preparedness plans for Ebola and other very high-risk infectious disease?

In the "other" category, the most common responses were the emergency preparedness team, safety committees, the clinical laboratory, and the quality improvement team.

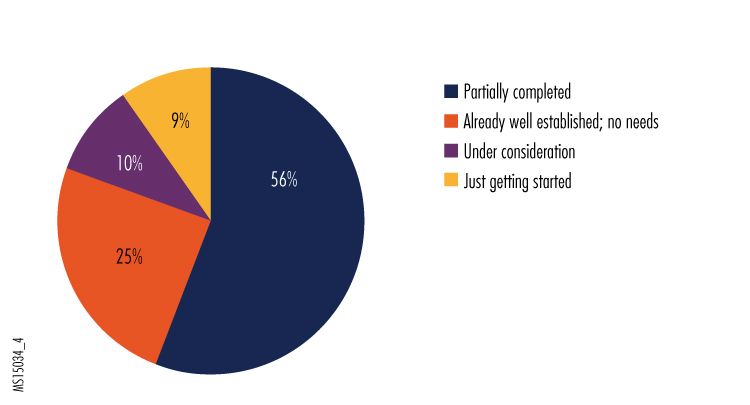

4. How would you judge the status of the equipment/technology portion of your organization's preparedness plans for Ebola and other very high-risk infectious disease?

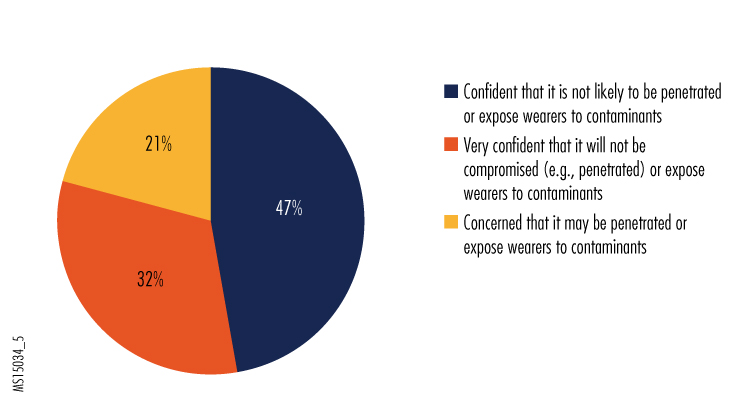

5. How would you rate the protection provided by the PPE used by your organization?

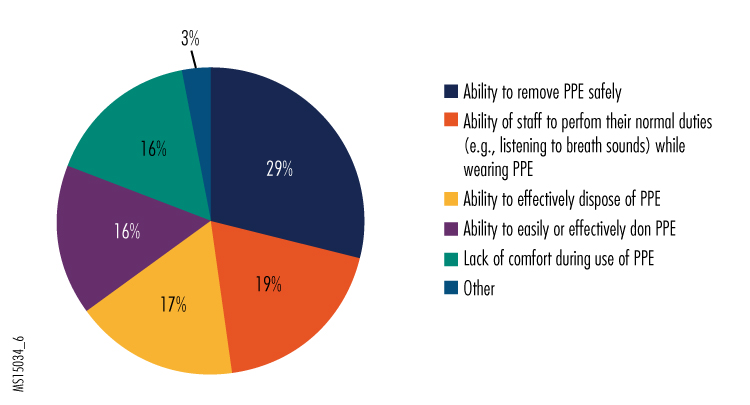

6. What concerns do you have (if any) with the use of PPE in your organization?

Given that the removal protocol recommended by CDC is very complex and involves many steps, it shouldn't be too surprising that two significant concerns people had about their PPE were safe removal and safe disposal. In addition, PPE training is evidently revealing the challenges of effectively completing some tasks, judging from the concerns that some expressed regarding the PPE interfering with clinical functions and being uncomfortable to wear throughout their shift, as well as from some of the "other" responses we received. We encourage hospitals to continue regular training exercises, both to maintain staff competence in wearing PPE and to explore different ways that clinical tasks can be conducted while doing so.

Additional responses in the "other" category noted how uncomfortable wearing the PPE can be and how it can affect concentration. It wasn't clear from the survey results whether use of PAPRs resulted in the same level of discomfort as wearing N-95 respirators. However, the continuous ventilation provided by PAPRs may help reduce discomfort during prolonged use, which may be why many respondents indicated that they preferred PAPRs. Hospitals might want to consider the use of the less expensive N-95 respirators for shorter-term and less hazardous uses (e.g., protection while repairing equipment).

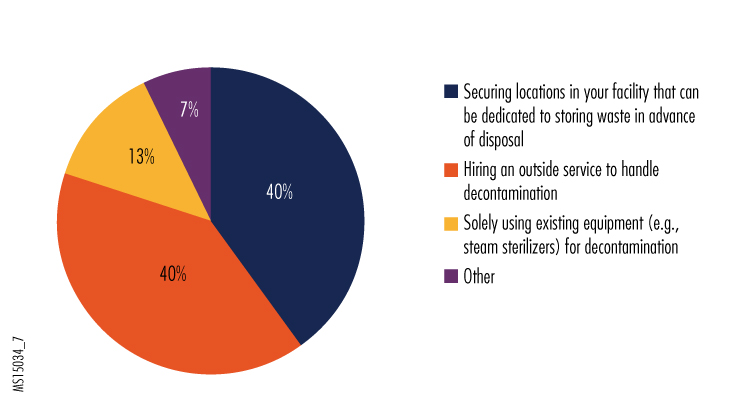

7. Considering restrictions on transportation of hazardous materials and the large volume of infectious waste that can be generated in treating an Ebola patient, how do you plan to handle waste that is infected or potentially infected with Ebola?

Something we didn't ask was how the facilities that were putting waste in dedicated storage (who made up 40% of respondents) would ultimately dispose of it. Having adequate safe storage might alleviate the pressure to quickly deal with mounting piles of waste. Presumably a facility could later decide whether to attempt using decontamination or disposal equipment on-site or to engage an outside service.

The most common response in the "other" category was that respondents didn't know how they will handle waste disposal. Judging from such responses, some hospitals have not placed as high a priority on how to dispose of waste as they have on PPE selection decisions.

8. Have medical product vendors promoted new products that help combat Ebola to your organization? If yes, what type of products have been promoted?

This was an open-ended question, and as might be expected, there was a wide range of responses. Nearly half were related to PPE. Respondents stated that products were promoted by their manufacturers as providing enhanced protection or as being especially fluid resistant. Often when buyers are fearful about their safety, product vendors will try to exploit that fear to promote their products.

When selecting PPE, it's important to consider the trade-off between comfort and fluid protection. When feasible for the expected tasks, we suggest that hospitals select PPE designed with impervious or reinforced regions for areas of the clothing where the risk of fluid contact is highest, and with less fluid resistance in areas unlikely to be exposed to fluids (e.g., the back of a gown).

Many other responses indicated that hospitals are considering room-disinfecting systems, such as the UV light systems being promoted to sterilize rooms. UV light systems are a good adjunct to conventional decontamination, but bear in mind that they may not be effective if thick layers of fluids or soil are present, and that they will not reach surfaces that are in shadows. Chemical misting systems for room decontamination can also fail to be effective if fluids or soil are not first removed. CDC recommends that nonporous surfaces first be washed with a detergent solution and then treated with an appropriate disinfecting agent registered with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Hospitals should follow this recommendation before using a room decontamination system.

9. Please provide any other Ebola-related concerns or comments you have regarding the acquisition and/or use of medical devices and PPE.

This was also an open-ended question that elicited a wide range of comments. Many of the responses related to concerns about whether reusable equipment could be safely decontaminated. Concerns were also raised regarding what types of PPE staff would have to wear to perform this decontamination.

CDC's guidance on decontaminating surfaces is applicable to reusable medical equipment. The Ebola virus has not been found to be resistant to common disinfecting agents, so if these recommendations are followed, hospitals should have confidence that the decontaminated equipment is safe for reuse. We advise hospitals to first consult the EPA web page that lists registered disinfectants that can be used against the Ebola virus, and then check with device manufacturers to determine which agents are compatible with their equipment. An additional consideration—when it won't interfere with equipment function—is to use draping materials to protect medical equipment from splashes or spills of patient fluids. If this is done, followed by wiping with an effective disinfecting agent, the recommended first step of removing gross debris with a detergent solution can be omitted.

Another topic that elicited many responses is the difficulty, noted earlier, in obtaining the PPE that hospitals have selected, as well as concerns about its cost. A number of people worried that PPE might go through significant price hikes because of the shortage, but no respondents reported experiencing this.

Others responded with concerns about the changing recommendations from CDC, especially regarding use of PPE. CDC has revised its recommendations for PPE over the last few months (e.g., adding the requirement that no skin be exposed and recommending the use of full face shields and hoods), apparently in response to lessons learned from the treatment of a few patients in U.S. hospitals. As those hospitals can attest, identifying best practices has been associated with a steep learning curve. At this point, however, ECRI Institute believes there should be less need for CDC and other authorities to make changes. Of course, we recommend that hospitals regularly visit the CDC website to ensure that their procedures are in line with current recommendations.

Respondents also said they had concerns about staff training. CDC advises hospitals to train staff on the use of PPE—with regular refreshers—to ensure that competence is maintained. Given the complexity of the protocols that have been recommended for putting on and removing PPE, we believe periodic retraining and drills are critical to being properly prepared.