Prevalence of Adverse Events

The prevalence of adverse events in long-term care settings is a primary driver of the need for effective reporting and response. For example, a 2014 study by the Department of Health and Human Services' Office of Inspector General (OIG) found that an estimated 22% of Medicare beneficiaries experienced adverse events in skilled nursing facility stays of 35 or fewer days; the same study also reported that an additional estimated 11% of patients experienced temporary harm events. Physician reviewers found 59% of the events "clearly or likely preventable." (OIG) It has been estimated that approximately 8 million adverse events occur annually in nursing homes. (Wagner et al.)

The human and organizational costs of adverse events are staggering, with estimates of preventable errors in the United States ranging from $17 to $29 billion per year in healthcare expenses, lost worker productivity, and disability. (Hoppes and Mitchell) The 2014 OIG study found that follow-up hospitalization costs related to adverse and temporary harm events in skilled nursing facilities totaled an estimated $2.8 billion per year. (OIG)

Several challenges associated with the long-term care environment have been identified as contributing to the prevalence of adverse events in this setting, among them resident frailty, complex needs of residents, insufficient organizational resources, and frequent transitions of residents between settings (e.g., rehospitalization). (Vogelsmeier)

Underreporting

Despite the undisputed prevalence of adverse events and near misses, underreporting is a significant concern and compliance varies among different groups of reporters. Although a variety of stakeholders are prospective reporters, including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, support staff, patients, and families, there are notable differences in who actually reports, and at what frequency. Researchers have found that most reports are submitted by nursing staff, who believe that safety reporting is one of their job responsibilities; pharmacists are also frequent reporters for medication-related events. However, physicians and medical residents, who are in the position to have intimate knowledge of events and their sequelae, tend to be less familiar with what and how to report, and may believe that reporting is not part of their job; therefore, they typically contribute a very small fraction of reports. (Heavner and Siner; Mansfield et al.)

Research has also shown that fear of liability and organizational and managerial barriers exist, and staff members are often apprehensive about punitive and adversarial approaches taken by employers. (Naveh and Katz-Navon)

Barriers to Event Reporting

Numerous barriers to event reporting have been identified, with consistent themes noted worldwide. For example, an international panel of patient safety experts identified the following five key challenges limiting the full potential of incident reporting systems at the organizational level (Mitchell et al.):

- Inadequate engagement of clinicians

- Inadequate processing of reports

- Insufficient action in response to reports

- Inadequate funding and institutional support

- Insufficient leveraging of evolving health information technology developments

Individual perceptions and experiences often reflect factors cited at the system level. Barriers to effective event reporting for clinicians include the following (Evans et al.; Schectman and Plews-Ogen; Uribe et al.):

- Lack of:

- Anonymity

- Understanding of need to report near misses

- Sufficient time to report

- Clear reporting protocols

- Available computer and/or report forms

- Feedback on action taken following report of event

- Physician involvement in the system

- Belief that:

- Reporting does not contribute to improvement

- An incident with low level of harm or no harm is not significant enough to report

- Fear of:

- "Telling on" another healthcare worker

- Punishment and lawsuits

Such barriers are widespread. In both U.S. and Chinese studies, for example, nurses reported thinking that mistakes are held against them, and that event reports identify the person as the problem rather than the occurrence (i.e., the staff member involved will be personally blamed). (Kear, Ulrich; Wang et al.).

These barriers—and strategies for mitigation—are discussed in more detail in

Action Plan. See

Staff Perspectives on Underreporting of Events for candid quotations about barriers to event reporting from frontline staff.

Develop Organizational Framework

Action Recommendation: Define events to be reported and identify roles of stakeholders.

Defining Events

Disparities in concepts, definitions, and classification systems of the types of events that should be reported, as well as different data capture methods, make measurement of preventable harm a challenge. However, establishing consistent definitions, classifications, and measurement processes allows for accurate, consistent, and efficient identification of events as reportable. Consistent definitions also lead to rapid responses, facilitate prevention by mitigating systems issues, allow for standardized measurement of events and prevention strategies, and help support regulatory requirements for collection and categorization.

To standardize event reporting, the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) developed

Common Formats, a no-cost, publicly available taxonomy that can be used by providers and patient safety organizations (PSOs) for reporting safety events that occur in acute care hospitals and nursing homes. It describes patient safety concerns as follows (CMS):

- An incident is a patient safety event that reaches the patient, regardless of whether or not the patient was harmed.

- A near miss (or close call) is a patient safety event that does not reach the patient.

- An unsafe condition is neither an incident nor a near miss but is a circumstance that makes the occurrence of such an event more likely.

Occurring more frequently than adverse events, close calls frequently go unreported. Experts estimate that for every serious event that occurs, there are 29 minor injuries and 300 near misses. In accordance with best practices for risk management, reporting of close calls—or near misses—is promoted as part of the Common Formats reporting tool. Near misses are an information-rich resource; the sheer volume of near misses means that systemic problems can be identified with far less than 100% reporting, and without any patient or resident harm. (Marks et al.)

See

ECRI Resources for Reportable Events for a list of serious reportable events that are paired with related resources for mitigation.

Defining Roles and Responsibilities

The role of stakeholders is quite clear: anyone who witnesses or discovers an event should make or contribute to the report. This means an event that involves multiple stakeholders should allow input from all involved, including the patient; family members; frontline, case management, and patient relations staff; and surgical team. Such "participants" should be listed on the event form, their roles described in the event narrative, and contact information provided for follow-up, if needed.

Event Forms

As of March 2022, there is no consistent format for reporting race or ethnicity of individuals involved in events, rendering such information underreported, and therefore, tracking racial or ethnic healthcare disparities even harder. However, research suggests that such disparities are widespread in long-term care in general—a reality brought to light during the COVID-19 pandemic. See the following ECRI coverage of recent research concerning disparities in long-term care: To combat disparities in event reporting, ECRI recommends that all healthcare organizations examine the racial demographics of reported patient and resident safety events and root-cause analyses performed by the organization for serious events and determine whether racial or ethnic disparities exist in the types of events reported and analyzed. Organizations can use this information to design policies and work to eliminate racism and discrimination from within the organization. See

Bias and Racism in Addressing Patient Safety in ECRI's 2022 Top 10 Patient Safety Concerns for more information.

|

Typical event report forms (whether paper or electronic) contain demographic information on the individual involved in the event (see

Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Event Reporting for specific guidance), a brief narrative description of the event, and checkboxes for classifying the event (or occurrence) by type and category. Forms are marked "confidential" and should contain other introductory language as required to meet applicable statutory protections from disclosure. Event reports are usually supplemented with a follow-up report that contains more detailed information, causative factors, and corrective actions. See Internal Incident Report Form for Aging Services for sample content that should be addressed.

Internal Incident Report Form for Aging Services for sample content that should be addressed.

Reporting Policies and Procedures

All organizations should have written policies and procedures for event reporting that are approved and endorsed by the governing board. Event reporting policies should address what and how to report; specify timeframes for reporting, follow-up, and report retention; and staff responsibilities for each. See Internal Adverse Event Reporting Policy for an example.

Internal Adverse Event Reporting Policy for an example.

U.S. organizations should review policies and procedures in light of the U.S. Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act (PSQIA) protection provisions for "patient safety work product"—qualifying information such as adverse events and near misses collected and analyzed for the purpose of reporting to the PSO in the context of a patient safety evaluation system (42 U.S.C. §§ 299b-21 to b-26). Those interested in participating with PSOs—or those anticipating doing so in the future—-may need to reconsider how event reports are submitted and create a patient safety evaluation system in which event reports are collected (see

Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act for more information).

Affirm Choice of System

Action Recommendation: Choose an event reporting system based on ease of use and optimization features (e.g., interoperability with existing electronic health record system, dissemination of event report summaries).

Organizations should ensure that they have identified an event reporting system that will be appropriate for the population served and will work within operational constraints. Successful adverse event reporting systems are nonpunitive, confidential, independent, timely, systems-oriented, responsive, and include expert analysis. (Leape)

AHRQ has identified the following key components of an effective event reporting system, against which a current or prospective system may be evaluated (AHRQ):

- A supportive environment for event reporting that protects the privacy of staff who report occurrences

- The ability to receive reports from a broad range of personnel

- Timely dissemination of summaries of reported events

- A structured mechanism for reviewing reports and developing action plans

If the existing event reporting system is not providing the information needed to identify problem areas, analyze event trends, and make improvements, it is time to revamp or replace the system. Organizations may want to meet with current users in focus groups or conduct individual interviews to learn what does and does not work within the reporting system. Risk managers should compile a list of challenges identified by staff and work through the list to see how the most common and pressing concerns may be addressed.

A multipronged approach to refine and maximize the efficacy of reporting systems includes the following strategies (Hanlon et al.):

- Updating online systems, including response options and reporting intake forms, to improve compliance

- Hiring additional staff members to help providers meet reporting requirements

- Shifting from a regional to a centralized process to provide a more standardized approach to program management

- Implementing programs to recognize leading reporters

- Moving away from an approach focused on sentinel events to a broader patient and resident safety surveillance and improvement program

For organizations accredited by Joint Commission, sentinel events prompt immediate investigation and response and organizations are urged—though not required—to report them to Joint Commission. As such, Joint Commission has published sentinel event policy and procedures for the following aging care settings: |

Selection of any event reporting system should align with the organization's goals and capabilities for using the data, such as whether the data will be mapped or uploaded to a PSO or other external system, whether the system will be used to track multiple quality initiatives over time, how the system exports data, and whether the system helps identify sentinel events or those reportable under state statutes.

Ultimately, systems should be selected and updated with the goal of making reporting easier, ensuring that providers have quick and ready access to systems that are simple enough to use with minimal or no training. Leaders can also ensure that reports are linked to action by selecting reporting systems that code reports into specific areas, such as medication errors or wrong-site surgery, so that safety issues can be easily monitored and evaluated to provide the evidence needed to address them.

Once an electronic system is implemented or updated, it may be helpful to run simulations with the software, allowing the opportunity for a sampling of reporters who will be using the proposed system to give feedback on the system's usability and identify any trouble spots within the program.

Educate All Stakeholders

Action Recommendation: Ensure that all potential reporters understand why and how to report events.

Once a new or revised event reporting system is selected and leadership support is obtained, a great deal of education must be provided to clinicians, management, and staff. The risk manager should collaborate with quality improvement managers, information technology personnel, staff educators, and others when developing and providing educational programs. A train-the-trainer approach to education may be best for large, diverse, and geographically dispersed organizations. This educational style was identified as a key success factor in a case study on a systems approach to improving error reporting in one of the nation's largest not-for-profit integrated healthcare systems. (Joshi et al.)

Bearing in mind that both reports and follow-up are required for an effective event reporting system, training in the culture of safety and incident reporting should be required at the earliest possible point. (PSQCWG) When initial training is complete, subsequent training in error reporting systems during orientation of new hires is recommended. (Mandavia et al.)

ECRI's

Event Reporting Training Program can be used as a model for educating frontline staff.

Foster Just Culture

Action Recommendation: Cultivate an atmosphere that encourages reporting

without fear of blame and repercussions.

If an organization's culture is not conducive to event reporting, the system will not be successful, and underreporting will be likely. Therefore, event reporting systems must allow ease of reporting for staff, must be viewed as a positive contribution, and must show evidence of resulting change and improvement. Risk managers, in conjunction with clinical leaders and organizational managers at all levels, must strive to create such an atmosphere in their organizations. See

Culture of Safety: An Overview for more information.

Respond to Reports Accordingly

Action Recommendation: Analyze data and respond accordingly to improve clinical and operational processes.

Reporting of an event is just the beginning of a comprehensive response process; actions taken thereafter will determine the organization's ability to meet the ultimate objective of improved patient and resident safety.

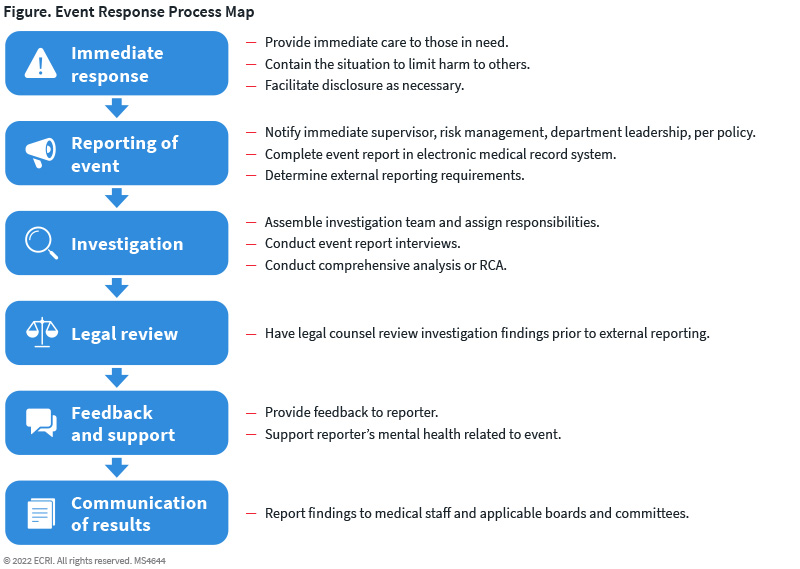

Figure. Event Reporting Process Map provides a full overview of the process, as well as ECRI's Postincident Response Algorithm.

Postincident Response Algorithm.

It should be noted that each organization's response plan will look and behave differently from others, depending on a variety of factors, including whether it is a single- or multisite organization; whether it is a stand-alone service line or continuing-care retirement community; what the organizational design is like—including positions and assigned responsibilities; and how the chain of command is structured. Generally speaking, however, the following guiding principles of event response for risk managers and investigators have been identified (Hoppes et al.):

- Operate within appropriate legal authorities (e.g., federal, state).

- Understand organizational culture and be sensitive to organizational ethics.

- Investigate with focus and purpose.

- Maintain the trust of colleagues, staff, patients, families, local authorities, and the media.

A successful review process must be expert, credible, and timely, with a balance of independent and appropriate content resources. Leadership from the risk management department is critical to ensure that evaluation, prioritization, and action regarding events are carried out effectively, including an immediate response addressing appropriate disclosure and the needs of the patient and their caregiver(s) (see

Incident Identification and Notifications in Aging Services and

Disclosure of Unanticipated Outcomes for more information).

In addition to follow-up for individual events, aggregated data must also be assessed to track overall system performance over time. Similarly, Joint Commission International (JCI) states that appropriate responses for accredited organizations and certified programs include the following activities (JCI):

- Conducting a timely, thorough, and credible root-cause analysis

- Developing an action plan designed to implement improvements aimed at risk reduction

- Implementing identified improvements

- Monitoring the effectiveness of the improvements

Given the prevalence of events and near misses, risk managers may not be able to address every occurrence—especially as increased awareness, educational efforts, system optimization, and cultural shifts result in more reports. Prioritization of characteristics such as level of harm, preventability, or regional/national priority has been suggested to ensure that the most meaningful reports are investigated and addressed thoroughly. Such focus may include events that occur most frequently, cause the most harm, or are of greatest concern, such as those on the National Quality Forum's list of serious reportable events. (Pham et al.)

Analysis

Without analysis and follow-up, event reporting is of little or no value. However, many facilities do not have robust processes for analyzing and acting upon aggregated event reports. (AHRQ)

Such an examination should be a "comprehensive systematic analysis," such as root-cause analysis (RCA), focusing on systems and processes. RCA is one of the most common forms of comprehensive systematic analysis used for identifying the causal and contributory factors that underlie sentinel events, if they do the following (JCI):

- Focus on systems and processes, not individual performance.

- Focus on specific causes in the clinical care process as well as on common causes in the organizational process.

- Repeatedly investigate in pursuit of the root cause.

- Identify changes that could be made in systems and processes that would reduce the risk of such events occurring in the future.

For more information on RCA, see the following ECRI resources:

Another common methodology—one that is possibly under-utilized or confused for RCAs—is apparent cause analysis, which is often used for medium or low-risk safety events and does not require the same level of resources as RCAs. See Comparison: Apparent and Root Cause Analyses for more information.

Comparison: Apparent and Root Cause Analyses for more information.

Other tools and methodologies are also permissible, such as:

- Human factors analysis and classification system

- After action reviews

- Debriefs and huddles

- Concise incident analysis

Regardless of the analysis method, events should be investigated by experienced professionals using a standardized approach to ensure that the review is thorough, and the process and results are credible. The standardized investigation process should include a formal, written, competency-based plan for event identification, investigation, and action, developed and agreed upon in advance. It should also balance the focus on and review of individual issues (e.g., error and contributing factors) with that of system issues (e.g., inadequate procedures, lack of available resources, and/or poor design). (Hoppes et al.)

See ECRI's

Incident Investigation in Aging Services for additional, more specific guidance.

Create an Action Plan

Born of the comprehensive systematic analysis, the action plan identifies the strategies that the organization intends to implement to reduce the risk of similar events occurring in the future. An effective action plan must address the following (Joint Commission):

- Actions to be taken

- Responsibility for implementation

- Timelines for implementation

- Strategies for evaluating the effectiveness of actions taken, including metrics to measure the effectiveness of the action plans

- Strategies for sustaining the change

If designed and used correctly, an event report will indicate the level of follow-up needed and the speed at which it should be performed. Like the report itself, documents generated during follow-up should be treated as confidential to optimize legal protection. At the same time, fear of discovery should not override the organization's responsibility to disclose the occurrence of an event or error to the patient, investigate the cause, and implement preventive measures to avoid recurrence (see

Legal Discovery and QAPI: A Tale of Two Risks for more information). A follow-up report should document management's process review and be designated as a patient and resident safety, quality review, or peer-review document as indicated.

Provide Feedback

Action Recommendation: Ensure that all stakeholders receive timely and comprehensive feedback on reported events.

Without feedback to reporters, all other recommendations for event reporting are meaningless. Feedback affirms reporter actions and facilitates learning; lack thereof is a major barrier to reporting and response. (AHRQ) Feedback also motivates reporting future incidents; there is a risk that reporters who do not receive feedback will eventually stop reporting, even when mandatory. (PSQCWG)

The World Health Organization (WHO) states that providing reporters with timely feedback is a best practice to promote improvement through learning. (Larizgoitia et al.) In addition to a reporter receiving timely feedback, managers should share reports with their staff. (Pham et al.)

In addition to direct feedback on specific situations, effective communication strategies to help encourage additional reports from frontline staff include the following (Marks et al.; McKaig et al.; Mansfield et al.):

- Stories posted on the organizational intranet

- Annual patient and resident safety fair events

- Periodic action reports from the patient and resident safety committee

- Safety events highlighted in monthly publications or quarterly newsletters

- Sharing lessons among departmental representatives and colleagues

- This could be achieved by making five-minute "pointer" videos that feature a healthcare provider (usually the individual who reported the issue) describing how the issue was identified and investigated and how an improvement strategy was implemented

- Provision of information to frontline staff by nursing and medical leadership

- Monthly "good catch" awards to reporters

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

42 CFR §483.25(d)(1-2). "The facility must ensure that the resident environment remains as free of accident hazards as is possible and each resident receives adequate supervision and assistance devices to prevent accidents."

42 CFR §483.75(a)(1). "Maintain documentation and demonstrate evidence of its ongoing [quality assurance and performance improvement] program that meets the requirements of this section. This may include but is not limited to systems and reports demonstrating systematic identification, reporting, investigation, analysis, and prevention of adverse events; and documentation demonstrating the development, implementation, and evaluation of corrective actions or performance improvement activities. . . ."

42 CFR §483.75(c). "A facility must establish and implement written policies and procedures for feedback, data collections systems, and monitoring, including adverse event monitoring."

Elder Justice Act

As part of the Affordable Care Act, the Elder Justice Act authorizes and imposes a comprehensive range of initiatives aimed at combating elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation. For long-term care providers (e.g., nursing facilities, skilled nursing facilities, inpatient hospice units), one of the most significant features of the Act is contained in section 6703(b)(3), establishing notification and timely reporting requirements for any "reasonable suspicion" of a crime (as defined by local law) against any resident of the facility or individual who is receiving care at the facility. "Covered individuals" under the Elder Justice Act include owners, operators, employees, managers, agents, and contractors of long-term care facilities. The Elder Justice Act requires these individuals to report suspected crimes to law enforcement within 2 hours in the case of serious bodily injury, and within 24 hours if the crime does not result in serious bodily injury. Penalty for failure to report can be up to $200,000. (42 USC § 1320b-25)

In August 2021, the U.S. Senate

introduced a bill to reauthorize the act, but as of this writing, no measures have been passed.

Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act

Through PSQIA, federally designated PSOs offer a protected legal environment in which providers in all states and U.S. territories may share information about patient and resident safety events and quality (referred to as "patient safety work product," e.g., events, data, reports) without fear that the information will be used against them in litigation. By participating in a PSO, providers may voluntarily and confidentially report their patient and resident safety and quality information to a PSO for aggregation and analysis and in return receive recommendations, protocols, best practices, expert assistance, and feedback from the PSO to improve the provider's patient and resident safety activities. For more information, see ECRI's

Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act.

PSQIA does not, however, eliminate the need for healthcare organizations to submit state-mandated reports of events according to requirements of state reporting systems. Mandated reports, once submitted to a state reporting system, are not privileged under PSQIA. (42 USC §§ 299b-21 to 299b-26)

U.S. State Law

In the absence of a national reporting system, just over half of states have instituted mandatory event reporting systems, which state authorities and accrediting organizations use as part of their safety oversight function, and which are typically restricted to sentinel events. (Naveh and Katz-Navon)

As identified by the National Academy for State Health Policy's 2015 report, 27 states and the District of Columbia have adverse event reporting systems, all of which are mandatory with the exception of Oregon. Many of those states incorporate at least a portion of the National Quality Forum's list of 28 serious reportable events to establish a more uniform set of criteria by which to report and act. (Hanlon et al.)

See

U.S. State Adverse Event Reporting Systems for an interactive map illustrating which states maintain adverse event reporting systems and specific information about the systems of those that do.

Joint Commission

In its

Sentinel Event Policy and Procedures, the Joint Commission defines a sentinel event as a patient safety event, not primarily related to the natural course of the patient's illness or underlying condition, that reaches a patient and results in death, permanent harm, or severe temporary harm. Other events that are considered sentinel include, but are not limited to, patient suicide, patient elopement, wrong-site surgery, and surgery on the wrong patient. (Joint Commission "Sentinel")

The Joint Commission strongly encourages, but does not require, reporting to the organization of any safety events that meet the definition of sentinel event. However, the Joint Commission's nursing care center accreditation standards oblige accredited organizations to provide internal systems for reporting safety issues, near misses, hazardous conditions, and sentinel events as part of a system-wide safety program (Joint Commission "Comprehensive"):

- Leadership standard LD.03.09.01, addresses the responsibility of leaders to establish an organization-wide safety program; to proactively explore potential system failures; to analyze and take action on problems that have occurred; and to encourage the reporting of adverse events and close calls ("near misses"), both internally and externally.

- Medication management standard MM.07.01.03 requires the organization responds to actual or potential adverse drug events, significant adverse drug reactions, and medication errors.

CARF International

CARF International requires accredited facilities to develop written procedures related to preventing, reporting, and responding to critical incidents. Accredited facilities must also provide a written analysis of all critical incidents, including sentinel events, to facility leadership. Examples of critical incidents from the CARF Standards Manual include the following (CARF):

- Medication errors

- Restraint or seclusion

- Resident injury

- Lapses in infection control

- Violence or aggression

- Wandering and elopement

- Abuse and neglect

- Suicide and attempted suicide